“Male Writers, Female Readers”

“Reader, You Married Him: Male Writers, Female Readers, and the Marriage Plot,” an essay by faculty member Alix Ohlin, appears in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

1.

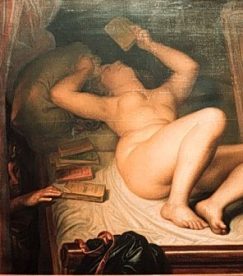

IN ANTOINE WIERTZ’S 1853 painting The Reader of Novels, a naked woman lies on her back, comfortably secluded in her boudoir, holding a copy of The Three Musketeers to her face. The sheets beneath her are in slight disarray. She looks like she’s having a good time. The painting, reproduced in Belinda Jack’s lively, engaging history The Woman Reader, shows a figure crouching in the shadows next to the woman, pushing yet another book onto her bed. If you look closely, you can just make out that the figure has horns; it’s the devil.

Wiertz was hardly a major painter, but his image of the female reader — sexualized, autonomous, perhaps in league with Satan — says a lot about historical anxieties regarding that figure. As Jack points out, representations of women reading are historically more numerous and more fraught than those of men. The female reader is associated with a dizzying myriad of contradictory qualities, from piety and maternal virtue to frivolity and eros. And nowhere is her role more contested than when it comes to the novel — a disquiet that continues even today.

Last spring, in The New York Review of Books, Elaine Blair published an essay on what she called “male losers” in fiction: male characters, written by authors such as Gary Shteyngart, Sam Lipsyte, and David Foster Wallace, who are presented as deeply flawed, narcissistic, unsuccessful in romance and otherwise. Blair speculated that these characters represent a form of preemptive self-criticism arising from anxiety in relation to an empowered and independent female readership. No author today, she wrote, can disregard the female reader:

For an English-language novelist, raised and educated and self-consciously steeped in the tradition of the Anglo-American novel, in which female characters, female writers, and female readers have had a huge part, the prospect of not being able to write for female readers is a crisis. What kind of novelist are you if women aren’t reading your books?

Whether or not you subscribe to Blair’s theory, it is certainly true that the history of the novel, and of novel reading, in English is inextricable from ideas and controversies about the female reader.

Women and men have long been presumed to maintain different reading habits and sensibilities, and the novel has always straddled the fault line of those differences. The question of who the female reader is — and what she wants — is in some ways built into the novel itself, whose reach as an art form expanded at exactly the same time as a female audience with the education and leisure time to read it. What’s interesting are the ways in which constructions of the female reader are both entrenched and shifting, constantly causing new fault lines to appear. In the 18th century, for example, women were assumed to like narrative, and men read for ideas; in the 19th century, women were thought to like detail and digression, while men read for the narrative point...[Keep Reading]…