Summer 2012 Residency Opening Remarks

MFA Program Director Debra Allbery’s opening remarks from the summer 2012 residency:

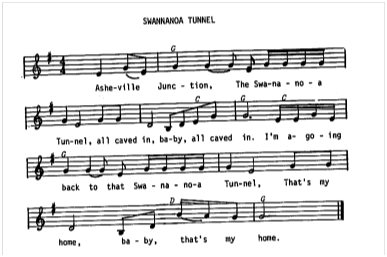

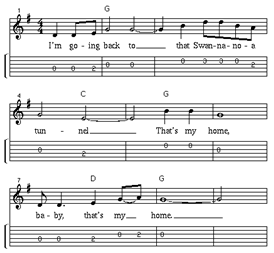

[The talk opens with the first two verses of “Swannanoa Tunnel,” as performed by Bascom Lamar Lunsford. A sample is available here.]

Provenance

“Swannanoa Tunnel,” also known as “Asheville Junction,” has a mixed ancestry: the local grafted onto the mythic. Cecil Sharp, a British folksong collector, documented it when he traveled through Buncombe and Madison counties in 1916-18. The isolation of these mountains made the area a rich repository of songs handed down from English and Scots-Irish ancestors—indeed, Sharp initially thought he’d happened upon a lost tribe of Elizabethans—and so he believed the song was an old English tune, mishearing the western North Carolina accent and transcribing Tunnel as Town-O, and hoot-owl as hoodow. But it was, of course, a work song, a collaborative and communal blues ballad—a John Henry variant with new verses layered onto its nine-pound hammer base, composed by the convict labor that spent two years digging the Swannanoa Tunnel in the late 1870s. At 1822 feet, this tunnel was the longest of seven struck by hand through these mountains to connect Asheville by railway with the outside world. Between 150 and 300 men died in the process; it’s thought that the particular cave-in referred to in the song happened in 1879, when 27 of the workers were killed.

Bascom Lamar Lunsford was a teacher, a country lawyer, a seller of fruit trees, a festival impresario, and ballad collector with a prodigious memory. He was born in 1882 near Turkey Creek, NC –what is now Leicester, just north of Asheville, and as a young man he traveled around western North Carolina, and later into Tennessee, Kentucky, and West Virginia, gathering the old ballads and their attendant stories. In 1949 the Library of Congress brought him to Washington to record over 300 songs and his stories of their provenance from his “Memory Collection”—the largest single collection drawn from any individual for their American folksong archive.

I’ve listened now to about 15 versions of this song—each distinct in its tone and tempo and order and selection of verses, and in its ratio of dark to light and past to present, in its proportion of leaving to return. It’s been recorded with the grunts meant for the swing of the hammer, and in a fluted and mournful Barbara-Allen soprano, in intricate high-lonesome clawhammer banjo instrumentals, and with driven 60s-folk-revival brio. Lament and boast and wish, it’s a song that, at least in Lunsford’s rendition and those that follow his lead, anticipates a return even as it documents the creation of the passageway for it; it sings of release even as it forges ahead into risk. Whistling in the dark, it shores itself up on the ballads of invincibility and endurance which—despite the John Henry legend itself being less than a decade old at that point—were known to all the workers. They were common currency, common ground—a charm to get them through: the hammer like no other that rings like silver, shines like gold; the hammer that takes on and defeat all challengers. The hammer that, thrown in the river, shines on.

Lunsford learned the song the same year Cecil Sharp first collected it—1916—and, to my ear at least, his unadorned, solitary front-porch version, with its lingers and rushes, its narrative leaps, sounds itself like memory, rising out of this land—the wind in the pines, the ghost hum in the rails. In some of the contemporary versions, the key is emphatically minor, the setting remains trapped in the grim present of the story: Men are dying in that tunnel where I’ve been, where I’ve been—there’s no return, and escape is only in the subjunctive: if I could gamble like Tom Dula, if I could rob them like some I’ve known, I’d throw my hammer in that mountain, and I’d be gone. What persists in the variants is the insistence upon and repetition of return—I’m going back—, and the permanence, the beacon, of that destination: in Lunsford’s version the first verse ends that’s my home, that’s my home; his last verse ends that’s no dream, that’s no dream.

My youngest sister and my brother have recently decided to trace my family’s lineage through Ancestry.com. Prior to this effort, pretty much all we knew of our forebears was that both our parents’ families came from England—and the odd but often-observed single detail that my great-grandfather ate his peas with a knife. My siblings have made several interesting discoveries—boar killers and landed gentry and theologians in stained glass, and even a poet, struck down in his prime, one of whose lines was borrowed by Wordsworth’s “Guilt and Sorrow”: And hovering round it often did a raven fly. However intriguing, these facts remain abstractions, given the absence of the stories that link them. However did we get here from there?

In my earlier years, perhaps like some in this room, I went through a stretch of imagining myself a foundling. I grew up in a devoted and supportive family, but my questions and passions—that is to say, my imagination—seemed to come from, and to be bound for, elsewhere. I felt caught in that same quandary Eavan Boland has written about her own sense of estrangement in her youth: “Unable to name the country I came from. Unable to come from it until I could name it.”

Because I was most at home in books, I sought my lineage there, but it would be years before I could firmly locate myself in my reading, first and foremost through Sherwood Anderson, whose hometown I shared. Wallace Stevens’ father once advised his children that the first key to success in life was to be “mighty careful in the selection of [your] parents”; Anderson was my first such chosen forebear. But before I met his work, my childhood was a long wandering though largely Victorian literature—tales of societal injustice seen through the eyes of mistreated animals, adventures with intrepid if irksomely sentimental heroines, stories of orphans and displacement and illness (ever the writer’s provenance), a land of black and white engravings. Its soundtrack was equal parts the old hymns our church favored, the chipper folk songs my mother sang while she cleaned house, my father’s Hank Williams albums. And, confined to the tiny, tinny rectangle of my transistor radio, Motown from radio station CKLW in Windsor/Detroit. The way minor seemed ever to shadow their major keys gave those songs a depth and heft and reach which drew me. “Even before they’ve been lived through,” Louise Glück has written, “a child can sense the great human subjects: time which breeds loss, desire, the world’s beauty.”

The first book of poetry I owned was a hand-me-down, a copy of Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses given to me by my great great aunt Ella —it was a 1919 edition with Rackham-like line drawings. Its cover was gone and the spine pulled away, exposing the signatures and stitching; the paper was rough and heavy, yellowed, deckle-edged. To borrow a phrase Welty used about her mother’s precious set of Dickens, it looked as if it had gone through fire and water. The verses seemed to me of a lost age drenched in a strange melancholy—the absorbed isolation and genteel privilege of those iambs and anapests, utterly removed from my own smalltown midwestern life and yet the introspective undercurrents, those solitary songs of contemplation, were familiar—the bed that was a boat, the shifts of scale in the land of counterpane, the pulse of windy nights, the looking-glass river. It felt less a storybook to me than a relic…an oracle. As Graham Greene has written, “In childhood all books are books of divination, telling us about the future, and like the fortune-teller who sees a long journey in the cards or death by water they influence the future.”

In listening to name the country we come from, we’re also, of course, listening for those beyonds in time and space, wider worlds we aim to bring into our own. One hears the call of story in Willa Cather’s account of the “intense intellectual excitement” she felt while listening to her Swedish and Danish neighbors as they churned butter or did their baking:

I had met ‘traveled’ people in Virginia and in Washington, but these old women on the farms were the first people who ever gave me the real feeling of an older world across the sea. Even when they spoke very little English, the old women somehow managed to tell me a great many stories about the old country. They talked more freely to a child than to grown people, and I always felt as if every word they said to me counted for twenty. … as if they told me so much more than they said—as if I had actually got inside another person’s skin. If one begins that early…no other adventure ever carries one quite so far.

Yusef Komunyakaa offers this account of the first poem he memorized, Poe’s “Annabel Lee”:

It seemed as if some deep part of myself already knew the rhythm and emotion of this name—a Southernness in its music. But “Annabel Lee” also ushered in a disquiet mystery and the strange feeling of eavesdropping on something almost taboo. At 9 I knew next to nothing about this kind of love, although I had been touched by an element of it in the blues that drifted out of the radios in our kitchen and living room. To know this great longing through words made me tremble inside my skin, and I believe it helped me traverse some new territory in my imagination. “Annabel Lee” was familiar and distant, ethereal and knowable, and not quite flesh.

Charles Wright’s brief essay on Emily Dickinson begins with a memory of Merle Travis’s “I am a Pilgrim,” and the “god-haunted, salvation-minded” music he listened to on the radio in the ‘40s. “The lyric, the human theme, remained the same, whether it was a coal-mining song, love song, wandering song or gospel song: death, loss, resurrection, salvation, leaving, leaving….” Wright was drawn to the “traditional and oddly surreal” music of A.P. Carter, songs which he said had “the point of view of someone watching, from inside, the world go on outside, and always aspiring to something beyond that world…And written as though the songs had been to that place already and come back with their messages.” Dickinson’s music, for him, belonged to that tradition—she was, he said, “the only writer I’ve ever read who knows my name, whose work has influenced me at my heart’s core, whose music is the music of songs I’ve listened to and remembered in my very body.”

The writer who knows my name, the discovery that is recognition. For Boland, the country she came from was found in Yeats. Reading him, she says, “I began to hear something different—the sound, at last, of a place where I might no longer be an imposter. A place that could be made exact in language and therefore hospitable to the very degree of estrangement I felt.” Identification thus becomes location and provides and shapes direction, even as it summons and shapes memory.

Such a discovery, to borrow a fine phrase from Seamus Heaney, and one that is remarkably suited to the dual perspective of our opening song: “an elsewhere of potential which seemed at the same time to be a somewhere being remembered…an escape route into some unpartitioned linguistic country, a region where one’s language would be…an entry into further language.” In the 1980s he took on the assignment to create a modern translation of Beowulf because, though he had no expertise in Old English, he had “a strong desire to get back to the first stratum of the language.” The work proved far more difficult that he’d anticipated—he felt the whole attempt (in a felicitious phrase for this talk) “seemed like trying to bring down a megalith with a toy hammer.” But instinct —“an understanding I’d worked out about my own literary origins,” –and one made all the more politically and culturally complex for a poet who had grown up in Northern Ireland—led him to persevere. The turning point for him ultimately came through the “etymological eddy” of a single word, þolian, which means to suffer, to endure. The word initially looked strange to him because it begins with the Old English thorn (þ, which makes a th sound); he looked it up in his glossary:

I gradually realized that it was not strange at all, for it was the word that older and less educated people would have used in the country where I grew up. ‘They’ll just have to learn to thole,’ my aunt would say about some family who had suffered through an unforeseen bereavement. And now suddenly here was ‘thole’ in the official textual world, mediated through the apparatus of a scholarly edition, a little bleeper to remind me that my aunt’s language was not just a self-enclosed family possession but an historical heritage, one that involved the journey þolian had made north into Scotland and then across unto Ulster with the planters, and then across from the planters to the locals who had originally spoken Irish, and then farther across again when the Scots Irish emigrated to the American South in the eighteenth century. When I read in John Crowe Ransom the line, ‘Sweet ladies, long may ye bloom, and toughly I hope ye may thole,’ my heart lifted again, the world widened, something was furthered.

I want to turn, finally, to Edwin Muir, as this talk had its origin in a passage from his autobiography. Novelist, literary critic, memoirist, renowned translator of Kafka, and a poet, Muir was born in the Orkney Islands, north of Scotland, in 1887—remote islands which life even in the late 19th century had changed little from two centuries before. Like our own isolated area at that time, Muir’s Orkney had little in the way of printed literature: “In our farmhouse we had the Bible, Pilgrim’s Progress, and Burns.” But also like western North Carolinians, Orcadians knew hundreds of ballads. “They were part of our life because we knew them by heart, and had not acquired them but inherited them.” They were sung, Muir said, “as if you had always been entitled to sing them ….The listener’s memory was his book, and he could turn over its leaves as we turn over our printed pages.”

By the time that Muir was 14, his father could no longer afford the rent of his failing farm, and so the family—father, mother, the two brothers and a sister still at home, and Edwin, made the decision to leave their agrarian life and move to Glasgow. The shift proved to be nothing less than an expulsion from Eden. “When I arrived [in Glasgow] I found that it was not 1751, but 1901, and that a hundred and fifty years had been burned up in my two days’ journey.” They lived in a tenement, worked in the factories, and within two years, his father, mother, and both brothers were dead. “The family…looked,” Muir said, “as if it had been swept by a gale.”

Muir’s subsequent employment was itself Kafkaesque, working in bone rendering plant; bones from the slaughterhouses were brought in and burned into charcoal which was then used for the refinement of sugar. He wrote in a diary entry, “I myself was still in 1751, and remained there for a long time. All my life since I have been trying to overhaul that invisible leeway.” In the years that followed those losses, through his own passion and determination, and with the support of a very strong marriage, Muir gradually created a life for himself in literature—first in journalism and literary criticism, then translation, three novels, autobiography, and finally, into poetry. It was a late arrival, a long struggle, but it provided, at long last, a means of crossing that leeway: “I wrote in baffling ignorance,” he said, “blundering and perpetually making mistakes.…

Though my imagination had begun to work I had no technique by which I could give expression to it. There were the rhythms of English poetry on the one hand, and the images in my mind on the other. ..I know now what Eliot means when he says that Dante is the best model for a contemporary poet.

A couple of decades ago, I taught a class called “Writers’ Beginnings” at a fine arts boarding school, in which we read the juvenilia and memoir pieces, along with the mature work, of several great poets and fiction writers. I gave the class, a small group of quite gifted fourteen-to seventeen-year-olds, the assignment to write a story or poem based on their earliest memory, and one of them startled me with his polite objection: “Miss Allbery, we’re not old enough to remember that far back.” The truth in that statement has come clearer to me over the years— increased perspective and a more finely-tuned attention have borne it out, an altered narrative distance, a greater patience. Edwin Muir expresses this shift in awareness—the perception he had of his own journey, as he finally began to write what he was meant to write—better than any other account I’ve found:

I realized that I must live over again the years which I have lived wrongly and that every one should live his life twice, for the first attempt is always blind. I went over my life in that resting space, like a man who after travelling a long, featureless road suddenly realizes that, at this point or that, he had noticed almost without knowing it, with the corner of his eye, some extraordinary object, some rare treasure, yet in his sleep-walking had gone on, unconsciously aware only of the blank road flowing back beneath his feet. These objects were still patiently waiting at the points where I had first ignored them, and my full gaze could take in things which an absent glance had one passed over unseeingly, so that the life I had wasted was returned to me.

“In living that life over again,” Muir goes on, “I struck up a first acquaintance with myself.”

Till, now I realized I had been stubbornly staring away from myself. In turning my head and looking against the direction in which time was hurrying me I won a new kind of experience… I felt, though I had not the ability to express it, what Proust describes … . “A moment liberated from the order of time” seemed to have recreated in me a man to feel it who was also freed from the order of time. …The bare landscape of my island had become, without my knowing it, a universal landscape.

Any talk of a writer’s beginning necessarily situates itself in medias res. Any account of provenance is necessarily more fraught and fractured and far-flung than the branches of any family tree can suggest. It’s in the etymology of the word itself, provenir, which, like an arrow headed in both directions, carries within it its origin as well as its going forth. How you got here—how each one of you came to be sitting in these chairs this morning—is a vital part of the charge, the intricate polyphony of this residency. The givens each of you bring to your individual enterprise, whether burdens or blessings, are the material of your making; one’s own naming necessarily involves both excavation and invention.

Every six months we go back to Swannanoa for ten days which reaffirm and inform and direct our dedication to our art. Your discovery of those writers who know your name, the deepening of your acquaintance with the continuum of tradition, your effort to locate and redefine your place within it, your recognition of how that inheritance feeds and guides the poetry or fiction you’ll create—those are essential elements of the work you’ll do in this program. You each stand now, or likely will at some point in the semesters ahead, at that position Muir found himself in, as he returned to his origins through the passageway he’d created for himself through his reading and introspection, and began finally to write what he was meant to: In turning my head and looking against the direction in which time was hurrying me I won a new kind of experience. It’s what Heaney expressed as he found, in the Old English word for endure, a connection between English literature and his own Irish past: an elsewhere of potential which seemed at the same time to be a somewhere being remembered. At the heart of such revelation is the awareness of the ways in which one’s own story might inhabit and give shape to the great subjects (time which breeds loss, desire, the world’s beauty)—the local grafted onto the mythic. We are on common ground here, in this valley which has held the old songs for so long. Wherever you’ve come from, this is your home.

WORKS CONSULTED

Bates, Milton J. “Selecting One’s Parents: Wallace Stevens and Some Early Influences.” Journal of Modern

Literature, vol. 9, no. 2, May 1982. 183-208.

Boland, Eavan. “On ‘The Wild Swans at Coole’ by William Butler Yeats.” First Loves: Poets Introduce the First

Poems that Inspired Them. Ed. Carmela Ciaruru. New York: Scribner, 2000. 49-50.

Cather, Willa. “Willa Cather Talks of Work.” Willa Cather in Person: Interviews, Speeches, Ed. L. Bent Bohlke.

Lincoln: U of Nebraska, 1986. 7-11.

Glück, Louise. “On ‘The Little Black Boy’ by William Blake.” First Loves. 86-88.

Greene, Graham. The Lost Childhood and Other Essays. New York: Viking, 1952.

Heaney, Seamus. Introduction. Beowulf. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2000. xxii-xxx.

Jones, Loyal. Minstrel of the Appalachians: The Story of Bascom Lamar Lunsford. Boone: Appalachian

Consortium Press, 1984.

Karpeles, Maud. Cecil Sharp: His Life and Work. Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 1967.

Komunyakaa, Yusef. “On ‘Annabel Lee’ by Edgar Allan Poe.” First Loves. 141-142.

Lunsford, Bascom Lamar. “Swannanoa Tunnel.” Ballads, Banjo Tunes and Sacred Songs of Western North Carolina. Smithsonian Folkways SF CD 40082.

Muir, Edwin. An Autobiography. St. Paul: Graywolf Press, 1990.

—. The Estate of Poetry. Introduction by John Haines. Foreword by Archibald McLeish. St. Paul: Graywolf Press, 1993.

—. Selected Letters of Edwin Muir. Ed. P. H. Butter. London: Hogarth Press, 1974.

Welty, Eudora. One Writer’s Beginnings. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Wright, Charles. “A. P. and E. D.” Halflife: Improvisations and Interviews, 1977-87. Ann Arbor: U. of Michigan

Press, 1989. 53-55.