New Work by Andy Young

A new essay, “Before the Inevitable Ending: Time, Nâzım Hikmet, and the Sweet Potato Boy of Tahrir Square,” by alumna Andy Young (poetry, ’11), appears online in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

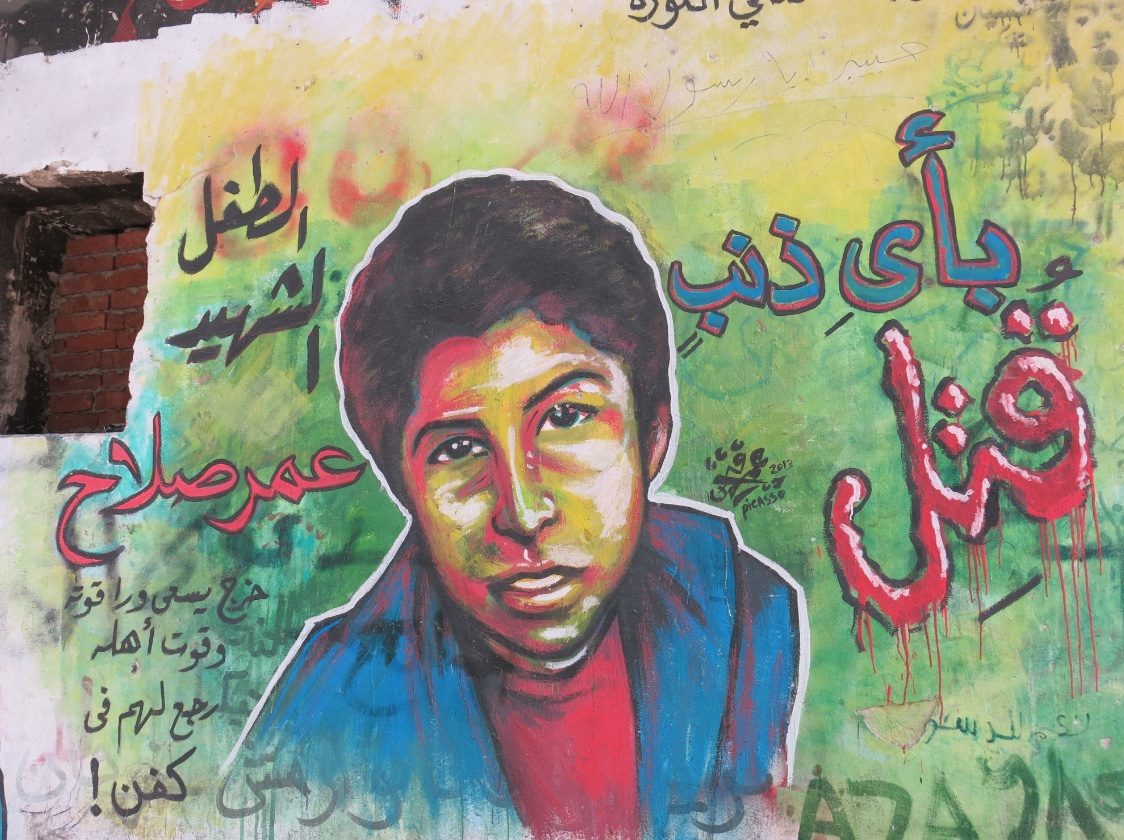

SINCE 2011, one of the mainstays of Tahrir Square, and the advent of its on-and-off occupation, is the presence of sweet potato sellers. Among the flags and protest banners, the throngs of citizens, and the hawkers of gas masks and cotton candy, the black metal potato stoves puff like small train engines. Twelve-year-old Omar Salah had been selling sweet potatoes for two years when he died in early February this year. He was shot twice by an Egyptian army conscript, “accidentally,” outside the gates of the US Embassy.

In Egypt, over the last two and a half years, thousands of people been killed by some type of authority attempting to contain protests — the police, the Central Security Forces, the Ministry of Interior, or, in Omar’s case, the army.

Regardless of who does the killing or holds the power, each death represents a stopped narrative, a ripple of grief, a person. As the deaths and their implications accumulate, as the blame is (or, in most cases, is not) assigned, the names blur and are replaced with numbers. Living in Egypt, I am constantly aware of, constantly overwhelmed by, the number or protests, the number of arrests, and especially the mounting number of the dead. Still, there was something about Omar’s death that stopped me, that made me want to know who he was. To remember his name.

It was a poem that did it, that stopped time for a moment, that cleared a space for Omar among the barrage of numbers and facts. In the aftermath of Omar’s death, a poem by the Turkish poet Nâzım Hikmet was circulating, in Arabic, on social media, because of the poem’s reference to Port Said. Port Said, at the time, was literally aflame after a pivotal court verdict, and would soon be placed under martial law. After some searching for an English translation (it is not included in the pivotal Poems of Nazim Hikmet), I was able to find a friend in the States to track the poem down and email it to me:

Light of My Eye, My Darling!

My Mansur of Port Said, aged thirteen or fourteen years,

barefoot, head close-cropped, sits shining shoes

by his box with its mirrors and bells.

High heels, soft shoes, army boots, walking shoes,

dusty, muddy, hopeless,

worn out, old,

mount the box with its mirrors.

Brushes take wing, red velvet glows,

high heels, soft shoes, army boots, walking shoes,

joyous, lively, young,

hopeful, shining,

step off the box with its mirrors.My Mansur, dark and skinny

like a date-stone,

my sweet Mansur

always sings the same song:

‘light of my eye, my darling!’…They set fire to Port Said, they killed Mansur:

I saw his photograph this morning in the paper;

a little corpse among corpses.

‘Light of my eye, my darling!’

like a date-stone.26 November 1956

Prague

translation by Ruth Christie

The poem seemed to be speaking to the present. When news of Omar’s shooting came out, it seemed as if the poem was written for him. But it is not. It’s about Mansur of Port Said — another little boy who worked instead of going to school, who was killed by the authorities. Most likely, he was killed by British forces, during their failed attempt to take control of the Suez Canal in 1956. Funny how a poem so rooted in a specific time and event can speak so precisely to the present.

Of course, it is also very depressing that, 57 years later, the narrative details still ring true. Mansur is part of the great dust of years between then and now, except that he has his name in a poem. His hair was cropped short. He sang as he worked. He was “dark and skinny like a date-stone.” Whether or not we believe Hikmet actually recognized the boy in the newspaper image, the chilling evocation of one individual fate, “a corpse among the corpses,” recalls the specific events that took place in Port Said; a boy is brought to life, and to death, in that short poem. Hikmet, a Turkish poet who spent much of his adult life as a political prisoner, plucked him from the anonymity of the relentless narratives that continue to charge across Egypt, and gave him a name, a life.

¤

“Poetry wishes to defray the damages of the inexorable, or at least to clarify […] them,” says David Baker in his essay “Lyric Poetry and the Problem of Time.” In revolutionary Egypt, there are plenty of inexorable damages, and keeping track of time, or of the events that punctuate time, is a dizzying effort. No one I know in Cairo could believe that the two-year anniversary of the revolution (now actually called “Revolution Day” on calendars) this past January 25 commemorated only two years.

This year, under now-deposed President Morsi’s rule, journalists such as Hani Shukrallah, who began the English-language newspaper Ahram Onlinein 2010, were forced from their positions. Photographers were arrested, artists charged with blasphemy. Sidewalks disappeared this year, the torn-up pavement used for ammunition in street battles against security forces. The bodies of activists surfaced, the marks of torture unmistakable on their corpses. Mohamed el-Guindy, a member of the opposition movement Popular Current and a Facebook administrator, was missing for days before he was found with burn marks on his tongue and throat, his face badly beaten. He died in the Cairo hospital in early February.

Some people have simply disappeared. This was almost Omar’s fate. Just like his death, the discovery of his body was accidental. Activists found him in Cairo’s only morgue, Zeinhom, near their friend, the murdered el-Guindy. A film also emerged: Omar was interviewed in a short documentary about child laborers, saying his wish, if he had one, was to learn to read and write. With six siblings and no money in the family, Omar had to work.

When he was shot, police officers were given orders, presumably by army authorities, not to take the body to the hospital to be registered, but straight to Zeinhom. As Amro Ali writes in his moving essay “The Maddening Betrayal of Sweet Potato Seller Omar Salah”: “In short, these are the accomplices in Omar’s death and cover-up: ambulance services, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Interior, and military. All feeling threatened by the corpse of a poor 12 year old street vendor.”

This summer, the Zeinhom morgue has been filled beyond capacity. A place known for filthy conditions and factual dubiousness (its keepers generally toe the party line), the temporary resting place for the dead has come to represent the ultimate sense of powerlessness within Egypt’s political climate, “a perfectly tuned factory of human misery,” writes Sherief Gaber in Mada Masr.

As story after brutal story — and name after name — accumulates, I have welcomed Hikmet’s poem and the way it has given me a container to hold, briefly, the grief for an individual life, for a poor child who worked instead of studied, for Omar, whose story resonates so much with Mansur’s. The poem has helped me to remember that Omar’s story, and the story of every individual, is just as important as the events that will one day be written about in the history books.

“Much of a poem’s style is designed to delay, to defer, to remind — to create a companion world where the reader may linger before the inevitable ending,” writes Baker. In Hikmet’s poem, Mansur’s brushes still take wing; he continues to sing that same song by that box covered in mirrors and bells. He is still “dark and skinny like a date-stone.” Before the inevitable ending.

Photograph by Andy Young

¤

For decades, Egyptian poets have responded to Hikmet’s Port Said poem with poems of their own. These poems, too, have been circulating on social media, giving voice to Port Said, its past and current tragedies. The poems, like Hikmet’s, have acquired new relevance in the present. Zein al-Abdin Fouad, or “Uncle Zein” as he’s called around Tahrir, is one of the poets who responded to Hikmet many years ago. He is still a fixture in the resistance, his words and his presence still part of the square during protests. He is still a regular at his favorite coffee shop downtown, where activists, writers, and artists sit smoking well into the very day-like Cairo night, arguing, laughing, and trying to continue their defiance, if not their optimism. When I asked Fouad about Hikmet’s visit to Cairo, he regaled me with stories of the two of them running around Cairo’s streets together, of Hikmet’s warm demeanor and his thirst to get to know the people in the street.

Fouad’s poem, “A Tale from Port Said,” written nearly a decade after Hikmet’s, shows a speaker who remembers the spirit of Hikmet’s earlier poem but struggles to recall the narrative details:

A Tale from Port Said

dedicated to the great Turkish poet Nazim HikmetThe story about Hassan was old.

They tore the newspaper. I didn’t see half of it.

A long time has passed,

and people have forgotten its title.They tore that paper and wiped the glass with it.

The glass in the story was green stained glass,

and in the story Hassan was tender and green.

In his eyes, the scent of iron,

stars, sea, night, fish,

music of a simsimeyah throwing its net over the water.His heart was a heavenly apple.

He roamed the coffee shops with his little box in his hand.

When he shined the shoes the streetlamps sang.

Port Said was hennaed, waiting for her groom.They sell the moon in commercials.

They sell the air.

They pack dynamite in medicine jars

and poison in pacifiers.

They came out at dawn to put out his song.

They steal the sun that rose with his smile;

he was among the victims of Port Said.When I laid out the story to my friends, they said to me:

the one who told this story was named Nazim,

and the boy was not Hassan.

The boy was Mansur (“the victor”) and he was victorious.

I said to my friends: the times have blended inside my heart,

and this morning, my window was broken.

I used the rest of the story to block the wind.1964

Years have passed since the events of the original poem, and the speaker reflects on a present that seems an even more heartless time: “They sell the moon in commercials. / They sell the air. / They pack dynamite in medicine jars / and poison in pacifiers.” What, the poem asks, has become of the story of the boy? “The times have bent inside my heart.”

In Fouad’s poem, time erases the facts. The boy’s life becomes part of just another story in a newspaper used to cover a broken window. “A long time has passed / people forgot what it was called.” What Fouad’s speaker loses in narrative detail, he adds in specificity of place: the sea, the streetlights, the simsimyeah, a traditional instrument that is a staple of the folk music of Port Said. In the boys’ eyes are the elemental images of the port city itself: “stars, sea, night, fish,” bringing the city to life.

“The boy was not Hassan / the boy was named Mansur.” Hikmet’s insistence on naming one of the dead gets subsumed to the city’s details in Fouad’s poem. As the names blur, the struggle of Port Said comes to the fore, a struggle that continues. “Port Said, its residents say, is a city of mourning,” Bel Trew reported recently in Ahram Online, “a city condemned.”

¤

Hikmet, who composed his best work in prison, aspired to write words in dialogue with the street. “I’m a poet — / whistling down the boulevards / I carve lightning shapes / of my poems / on city walls.” (translation by Mutlu Blasing). Though Hikmet was politically outspoken (and what we might now call an “activist”), it was ultimately his words, and the light they shed, that sent him to prison and, later, to exile. In many ways he is a poet of the moment — his was a time of worldwide uprisings, including revolution his native Turkey — always working to give voice to the powerless and to challenge those in power. He was, perhaps, the first person to be freed, in part, by a petition of artists. The “Save Nâzım Hikmet” committee of 1949 included such names as Pablo Picasso, Jean-Paul Sartre, Pablo Neruda, and Paul Robeson. Perhaps most strikingly, Hikmet never completely abandoned his optimism and his faith in the power of people to transcend oppression.

His poem “6 December 1945,” written in response to a specific event — the destruction of several newspapers in Turkey that were critical of the regime — could easily be a rallying cry for one of our contemporary resistance movements:

They are the enemies of hope, my love,

of flowing water

and the fruitful tree,

of life growing and unfolding.

Death has branded them —

rotting teeth, decaying flesh —

and soon they will be dead and gone for good.

And yes, my love,

freedom will walk around swinging its arms

in its Sunday best — worker’s overalls! —

yes, freedom in this beautiful country

¤

The late Salah Jahin, a beloved Egyptian cartoonist, dramatist, and poet whose words are still on people’s lips both inside and outside of the square, elegizes Hikmet by evoking his shoeshine boy from Port Said, among others, in another poem that has made the rounds these last months.

His heart was a green apple, and he died a martyr.

Didn’t you discover him again

and find that his heart was iron,

your poems on his tongue like anthems?

Didn’t you find your poetry had been living all this time?

The poem suggests that, even as the casualties mount, there is something in the poetry that keeps living, stubbornly. Though the poem was written soon after Hikmet’s death in 1963, much of the poem feels eerily contemporary. Algerian revolutionary Ben Bella is evoked, as well as a Kenyon ruler reduced to the walls of a cell, and then to the oblivion of history. Hikmet the poet lives on in his words and, in Jahin rendering, “his heart” is alive on the ship docks of the Anatolian coast. But the man himself, Jahin laments, is gone: “A year ago, didn’t you come to check on the fields / then find them in the farmers’ hands?” The phrase, “a year ago,” repeated three times, resounds with disbelief and sorrow. The poem lamenting the loss of the man keeps the poet, and the struggle to name the dead, alive. Here is the poem in its entirety:

Elegy for Nazim Hikmet

Did you die of your old wound?

After we thought it was over,

Uncle Nazim healed, he was sitting in the garden

reading the paper, writing letters.

Now they say: he’s dead.Didn’t we think it was over?

Didn’t we erase the jail cells with the smiles of our eyes?

Didn’t we bring you your medicine from India, China, Japan

from the countries of snow, Padang, Ceylon,

from here in Cairo?

Didn’t you wake and walk and come to pay us a visit?

A year ago, didn’t you come to check on the fields,

then find them in the farmers’ hands?

A year ago, didn’t you come to check on the factories,

then find them in the hands of the workers?

the boy in your poem “Port Said?”His heart was a green apple, and he died a martyr.

Didn’t you discover him again

and find that his heart was iron,

your poems on his tongue like anthems?

Didn’t you find your poetry had been living all this time?Why did you die, Uncle Nazim

before Izmir sang for you?

You should have lived.

Everything has its time.

Jomo Kenyatta—do you remember him?

He was your partner in the cell’s darkness.

A few years ago both of you were

our bitter tears,

our sad free hearts.

Didn’t he rule Kenya in the name of millions?

Didn’t Ben Bella walk out of the jail holding high the Algerian flag?

And Yemen got its day.

But you are the poet.

Your gentle heart—patient, in pain—

is still in Istanbul,

working on the docks

with all the sailors,

still in Anatolia, talking with so and so

still struggling with hope

still singing Ya Eini Ya Habibi…the Macadamia tree is thirsty beside the Dardenelles.

Its dry branches have turned to daggers.

You are the poet.

Your heart is that immigrant bird that embraces it and dies.

Oh great Nazim—

the wound that you died of is not the old one.

The “immigrant bird” at the end of the poem evokes an Egyptian myth about the Malek El Hazeen, a bird that chooses its own death by flying to its highest point, singing its sweetest song, and then impaling its heart on the branch of a tree. By equating the poet with the bird, Jahin suggests that Hikmet died in service to some greater ideal. Read in the current context, it is hard not to see the goals of the revolution as equally valiant and doomed.

Jahin’s placing of Hikmet in the context of his country and his ideals fixes him against the oblivion of time, just as Hikmet’s poem plucked the child of Port Said, killed in 1956, from complete anonymity. We should mourn the dead. But first we must name them. Omar, the sweet potato boy, whose death stood for nothing, should at the very least be remembered. So many more have been killed in the streets of Cairo since then. Some had written their own names on their arms so their mothers could be told. Hikmet’s poem, written from distant Prague, helped Egypt remember one of its own dead children. In naming Mansur, we remember Omar Salah.