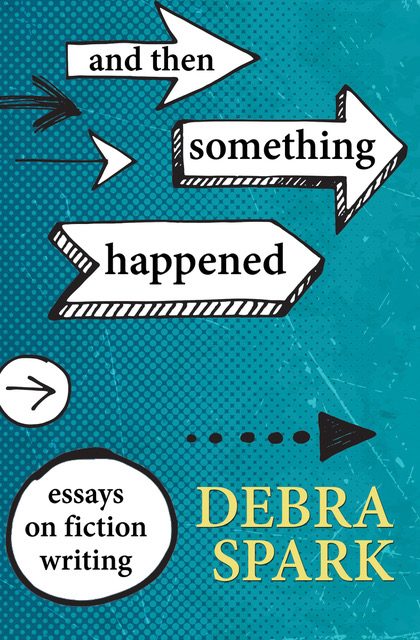

AND THEN SOMETHING HAPPENED: A new book of essays on fiction writing by faculty member Debra Spark

An excerpt from the essay “In Bed With a Book”

The first time I taught at Warren Wilson, I found myself traveling down a North Carolina highway with a group of writers I greatly admired. It was dinner time, and, after a day of classes, we were headed out for a meal. Because I had said, “Boys in the front, girls in the back,” as I folded myself into the car’s backseat, I had an urge to say something that might make me seem, however vaguely, like an adult. You don’t get to be an accomplished writer without being a passionate reader, so I asked my companions what made them readers, and they all had the same answer: “My mother.”

The first time I taught at Warren Wilson, I found myself traveling down a North Carolina highway with a group of writers I greatly admired. It was dinner time, and, after a day of classes, we were headed out for a meal. Because I had said, “Boys in the front, girls in the back,” as I folded myself into the car’s backseat, I had an urge to say something that might make me seem, however vaguely, like an adult. You don’t get to be an accomplished writer without being a passionate reader, so I asked my companions what made them readers, and they all had the same answer: “My mother.”

Rick, the driver, said that when he was young, his father abandoned the family, so his mother had to work all day. His grandmother served dinner at five o’clock, the hour when his grandfather returned from work. “She would not,” Rick said, clearly still amazed, “wait on dinner. She would not wait on dinner.” When Rick’s mother came home, she had to cook her own dinner, clean up, wash the family’s clothes (by hand), and tend to her son. The last thing she did each day was climb into bed and read for an hour. “It gave me the idea,” Rick said, “that reading was something to look forward to. A pleasure.”

My mother tells me that when my twin sister, Laura, and I were little, we would go to the library and each pick out ten books. Back home, flanking her on the living room couch, we’d make her read through all twenty at a sitting.

I trust my mother’s memory. I’ve seen photographs of just this scene, but I don’t remember experiencing reading as a pleasure until I was older. As soon as reading was something I could do (as opposed to something that was done for me), reading became a matter of ambition. In first grade, I felt humiliated by my place in the intermediate-level reading group. In third grade, when we were given a reading wheel to fill out—you colored in a square for each book you read—I gave myself headaches trying to read one hundred books in a week. I hunkered down with Shakespeare’s As You Like It in fourth grade (not that I understood a word) and took—what can I say, it’s true—Crime and Punishment to camp.

All this embarrasses me now. In the car in North Carolina, when I started to rant about my own impure motives for reading, another passenger politely quieted me: “But look where it got you.” And he was right, right mostly to shut me up, since it wasn’t really ambition that made me a lover of books but my mother and, as with Rick, an image of my mother reading in bed.