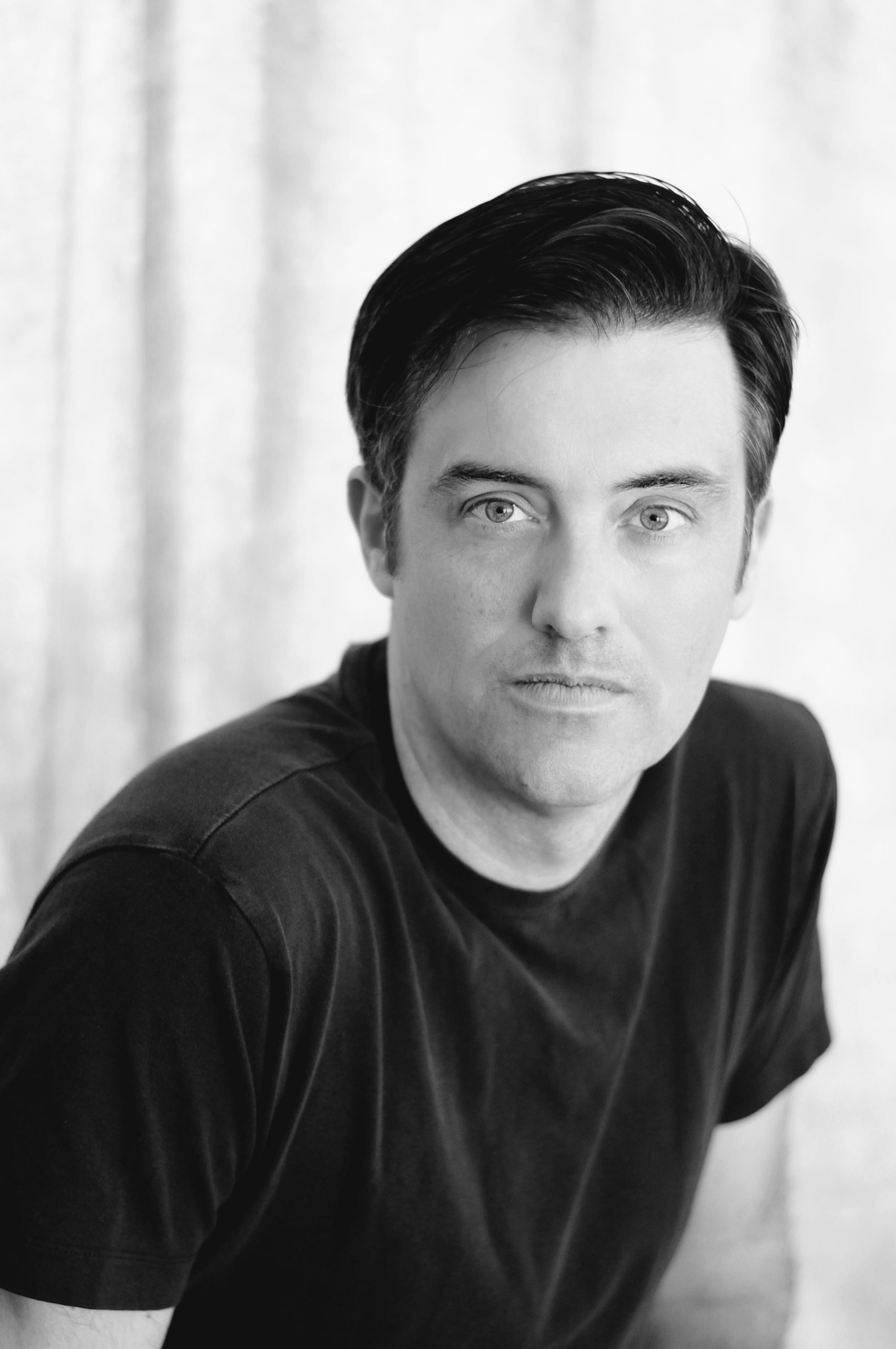

“Flight,” by Liam Callanan

Fiction faculty member Liam Callanan was recently featured in the LEON Literary Review. Read an excerpt of “Flight” below:

Flight

This is Mona’s favorite public market in Europe. She buys mint here, just to hold it, smell it, remind herself that yes, she’s landed, she’s actually here, in Rome.

Here, too, is the stall with the man she flirts with and the other man who flirts with her, and his wife, white-haired, seated, shelling beans, who never fails to reach for her hand and hold it tight and tell Mona what wonderful skin she has. And then she gives Mona a bean and bends back to her work—the bean is the woman’s signal that their exchange has ended and it’s time for Mona to move on—and good thing, because Mona would be susceptible, like Jack of beanstalk fame, to giving this old woman everything, anything, in return for another magic bean. The first time she gave her one, Mona stealthily pocketed it. The woman gave her a sharp glance, mimed it going into her mouth. So this Mona did. It tasted green and waxy and meaty and mealy and salty. It tasted like she was eating dirt. It tasted like a rebuke: never cook a vegetable again; always eat us raw.

Mona is American, 51, visiting (always). She’s breaking up today with Massimiliano, Italian, local, whose age she never did learn but whose tastes she knows well.

She thought to make a show of her announcement, meet him at, say, a real convent, but while scouting one, she got cold feet at the door. When a nun on her way inside asked, “can I help you?” Mona ran away, and found herself here, this market, again.

It’s the damn arrows. Painted on the pavement by someone who understands aviation. Has to be. Yellow arrows to the sides; white down the middle. Just like an airport: taxiways, runways.

The market, a mix of indoor and outdoor stalls, would have drawn her anyway: there’s always a musician, a rotating cast, some of whom the vendors tolerate less well than the others. There are two young men who not only look alike but, she’s learned, are actual twins who sell cheeses whose names and descriptions are untranslatable to her, though her Italian is decent after so many trips. The word purple always comes into the conversation for reasons she can’t identify—the cheese is not purple nor its rind—but she buys it because Massimiliano loves it.

Massimiliano loves rabbit, too, and that’s available, but she won’t buy it because, rabbit. And so she looks at the chicken and the duck and further on, the lamb—this is no better, so it’s on to the salt cod stand where everything, even the fishmonger, seems to have succumbed to a saline hoarfrost.

She runs her tongue around inside her mouth, along one row of teeth, then the other. They will eat first, a simple salad that he will dress and then they will undress and then they will make love. He is more attentive to her than any man she’s ever slept with, kind, tender but not tentative. She will miss that. And the wine after, tiny globe glasses right there in the apartment or more often, downstairs at the shop. And then he will look at his watch, unless she looks at hers first, which she tries to, to show that she, too, has obligations, another life, plans. And he will signal to pay. This she never interferes with. In her twenties, with other men in other cities near other oceans, she interfered with this part of the meal all the time. She’d grabbed checks out of presumptuous waiters’ hands. Out of dates’ hands. Cheap meals, expensive ones. She could pay! And she did.

After their wine, she and Massimiliano would kiss, one cheek, then the next. To anyone watching, they could be cousins, but for the additional second it takes for their hands to part. Then he would be gone, up the stairs and into his building, and she would look at the market packing up. The men in bright coveralls with the miniature garbage truck sweeping through the market, missing more than they get. Frilly, plate-sized leaves of lettuce would have affixed themselves to the cobblestones, sanpetrini, petite saint peters. Wrapped in lettuce, they look like bright green gifts and complement the red, red pedestrian-punished tomatoes (always present; no other market item sacrifices itself so readily). Left behind: paper and plastic and smears of gelato and pockets of water wherever anyone has half-heartedly slopped a bucket across the pavement.

The market, like its products, ripens over the course of the day. She’s come early on occasion, shopped, and then sat outside one of the cafés on the square, and so she knows what the square smells like when it starts, which is fresh and crisp and wet. She has long been tempted to sit at the rival café across the square—where they’ve never sat together; Massimiliano, like all good Romans, lives a life bracketed and buffeted by years-long feuds, and one concerns the café across the square—but she has no feuds, only curiosities, and one of them is what his ex-wife looks like. He has seen pictures of Mona’s daughter, Audrey, she has seen pictures of his boy and girl. Their beauty makes clear their mother’s. Audrey has her father’s eyes. Neither mother nor daughter has seen him for months.

Ostiense was more of a working-class neighborhood when Mona first came to Rome, years ago. It was the home to the gasworks and a massive transit center. There were no tourists here. There was nothing to see. The Colosseum was only a mile away, but then, in Rome, everything is closer than it seems; distances shrink the longer you’ve been in the city. Massimiliano used to live a 45-minute walk from where she usually stayed. He still does, and the walk still takes 45 minutes, but she always arrives before she realizes it, before she’s ready.

Read the rest of this story here: http://leonliteraryreview.com/issue-11-liam-callanan/