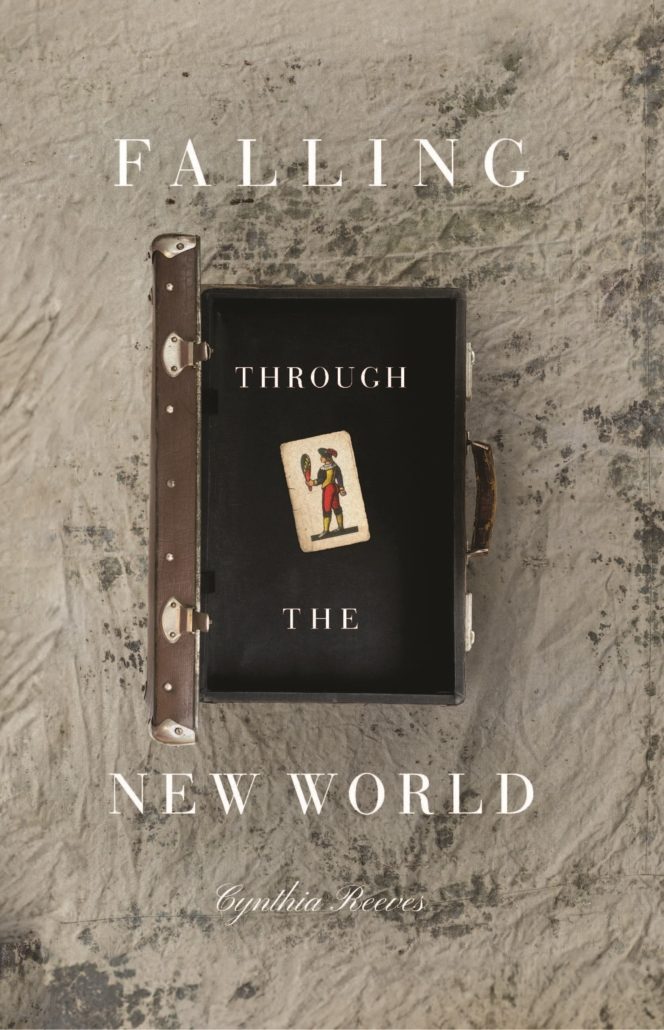

Read an excerpt from Falling Through the New World, the new novel in stories from Cynthia Reeves (Fiction ’06)

“Falling Through the New World”

I. BEFORE

Let’s start from the Piazza Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, whose name is longer than the piazza is wide, just a patch of earnest green, and a stone bench where the gossips debate our village Roccamaro’s unfolding history, and three spiny blackthorn trees profuse this time of year with delicate white flowers. Let’s start here, in front of the church of San Ponziano. Let’s greet the toothless gatekeeper who tolls the bell at noon each day, and dusts the Virgin’s shrine, and pockets the wedding coins rained down upon each happy couple to safeguard their future. Let’s look across the empty square to the Desiderios’ home, where Vincenzo Desiderio, my own Vincenzo, grew up. It’s the pale bronze stucco house, just there, the one with purple bougainvillea framing the alcoved doorway.

When Vincenzo’s mother was alive, she’d sit inside that doorway and read. The Inferno of Dante, The Tragical History of Dr. Faustus, all manner of Hell. This caused a minor scandal in our village, even though she found the books in the convent library. She’d read after the midday meal and, in the late afternoon, take her passeggiata to the convent down the hill. There, she’d trade that day’s book for another. She had a girl come in two days a week to take her laundry and clean the house, for she was a frail woman. No one knew quite what was wrong with her. She didn’t even breathe in the normal way.

At least that’s what the gossips said. In the morning, she’d kiss her husband good-bye outside their home and kiss hello when he returned at night—two more scandals, for no one but he worked during the long, hot afternoon, and no other couple kissed so passionately hello and good-bye. Signore Desiderio owned the Grande Magazzino, as he called it, a store that sold a bit of everything—bolts of cloth from as far away as England, tablecloths and antimacassars, hand-tailored suits and ready-made shirts, Milanese ties and Florentine belts, men’s felt hats and ladies’ straw ones, church veils that I wove for him on bobbins and pins, and even an exquisite French dress that no one could afford but stood on a dressmaker’s dummy in the display window for years, just to lure people into the shop.

Signore Desiderio’s four sons, Lelio and Michele, Arturo and Vincenzo, helped run the shop. Lelio was the one who traveled abroad to bring back the store’s wonderful oddities. And then all four brothers volunteered together for the Great War. Michele and Arturo were killed at Isonzo. As to Lelio and Vincenzo? We didn’t know yet what had become of them.

But that came after. Let me speak of before.

For my sister Ernestina and me, the Desiderios had their allure, the eccentric family with the four handsome brothers who were always quick with a wink, a ciao, Ernestina, ciao, Annina, le donne più belle di tutto il mondo. Michele proposed to Ernestina and Vincenzo to me in the chaos of their departure before they shipped out in 1915. Together she and I even made our wedding dresses after their deployment. A blessing Michele would never know that, like him, she died as a result of the war, of the Spanish influenza and not a bullet like one that killed Arturo or the strange gas that seared and sealed Michele’s lungs and fate.

How my mind wanders! Let me speak of before.

Before everything changed, we’d go to the Grande Magazzino together, Ernestina and I. The shop wasn’t far from our small home and olive grove at the bottom of the hill. Sometimes I’d bring Signore Desiderio a new veil I’d woven to sell in his shop, but always we’d bring him bottles of fresh-pressed virgin oil during autumn, the months of pressing. Papà would cluck his tongue at us, shameless girls, but would nevertheless offer us the dozens he made daily during harvest season. We took six bottles each day, only six. We’d arrive at the shop, breathless, fanning ourselves with our floral fans, even in December. Michele and Vincenzo would give each of us a piece of Ernestina’s favorite, vanilla torrone, and my favorite, almond croccante, from two tall glass jars that held only these candies, the only two they stocked. They had a third jar, always empty, from which they’d pull nothing and hand the bit of nothing to us. And every time we’d ask, “What is this air?” And they’d say, “It’s not air! It’s baci, the finest baci in all the world,” and they’d hold their hearts where we’d wounded them, and while we were apologizing, every day the same sugar-sweetened apology for our ignorance, they’d bend quickly to touch our hair and steal from each of us a chaste kiss.

I didn’t know then that my life had already moved into its after.

Falling Through the New World is out today via Gold Wake Press.

Cynthia Reeves on the web: cynthiareeveswriter.com