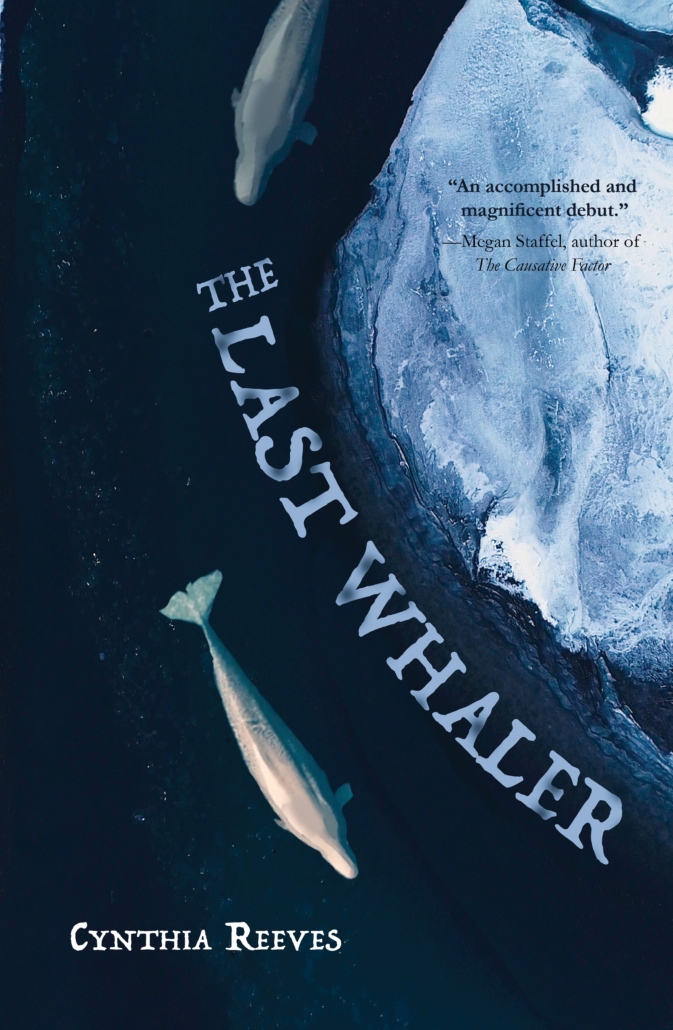

Read an excerpt from The Last Whaler, the new novel from Cynthia Reeves (Fiction ’06)

Opening to The Last Whaler

Kvitfiskneset

18 June 1947

Even on this desolate stretch of stony Arctic shore, on the archipelago Svalbard halfway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole, I must tell you there are consolations. Here the sun shines day and night from mid-April to late August. One can be fooled into believing summer will never end. Yet the summer solstice, the day of no night, is also the moment the sun begins its retreat. Only the seasoned Arctic dweller would notice the minute differences in the sunlight’s quality on either side of the solstice, the fulcrum upon which the season turns. Time and space converge, balance for a moment, then reel apart.

Norwegians celebrate Midsummer’s Eve by lighting a bonfire around which we dance and drink and sing. But like everything else in life, our joy comes tempered with the knowledge that sadness nips at our heels. Always. The bonfire reminds us that the sun is once again slowly sinking down. That in time, we’ll endure the companion days of no day. Perhaps if, on that evening by the bay, Astrid and I had thought of this precarious balance, this tipping point between the sun’s ascension and declination, we would have felt the undertow that foretold the time to come.

I want to relive that moment on the beach, the evening of our first Arctic Midsummer’s Eve celebration, 23 June 1937. To reach into time and space and wrench us back. To go forward from that instant and retrace with these words—mine and hers—the journey downshore from this whaling station to our private retreat at Haven. I want to add my thoughts to the weathered leather folio I hold in my hands—held together with fraying navy grosgrain, bulging with Astrid’s letters to our son Birk written in her elegant cursive—to bind my words to hers, present and past counterpointed.

As if words themselves will finally solve the riddle of my wife.

As if black marks on these white pages could bring her back.

As if a wash of ink will absolve me of my sins.

And so I’ve returned to my old whaling station on Kvitfiskneset, to the cabin I once thought of as nothing but a temporary harbor. Does everything in this life circle back to where it started? I’ve brought along the essentials. Food and drink to sustain me. Talismans for the coming Midsummer’s Eve bonfire. A rifle for protection against polar bears. And, of course, Astrid’s wedding dress.

Her wedding dress. Let me explain.

On that June afternoon, we covered the four-kilometer trek from the whaling station to Haven, away from the stinging smoke and foul odor of trying blubber. It was a Wednesday, normally a day of hard labor. But after a morning’s work, I’d given my whaling crew the rest of the day off. They had plenty of ale and food to celebrate while we escaped downshore to Haven. My name for it. Astrid called it The Leaning Tower because, after years of shifting foundationless in unstable permafrost, the old hunter’s hut pitched ever so slightly sideways. Many of these huts dot the archipelago, belonging to no one and everyone, refuges from the sudden unexpected—storms, impenetrable fog, polar bears. Itinerant hunters keep these cabins stocked with essentials for communal use and leave the doors unlocked to house anyone needing shelter.

Despite Haven’s slight lean and the bare trappings of its interior, it was in other ways a perfect jewel. Clad in weathered shingles, the hut boasted a large south-facing window that infused its single unfurnished room with light. Unlike our cabin at the whaling compound, the ground surrounding the hut was clear of offensive detritus. No animal skins dried on racks, no flayed polar bear or Arctic fox carcasses hung from wooden posts, no piles of discarded beluga bones bleached in the sun.

Clusters of yellow Arctic poppies and wood rush and a riot of purple and white saxifrage dotted the scree, as if a garden had been planted by some invisible hand. Astrid could name each flower: phylum, class, order, family, genus, species. She was, after all, a trained botanist. She’d earned a degree in biology at the university in Oslo, studied botany under Hanna Resvoll-Holmsen, and sketched Arctic specimens for her mentor’s definitive catalogue Svalbards flora. After graduation, she’d worked in Oslo’s Natural History Museum, assisting with collection curating in the fall and winter months when her family’s dairy farm outside Sandefjord presented fewer demands. Like so many women, she’d put aside her vocation to marry me and raise our children. She rankled when her girlfriends asked about her hobby as they passed their ordinary lives with their ordinary husbands. No doubt jealousy was involved. In small part, she’d accompanied me to the Arctic thinking to show them how wrong they were.

The Last Whaler is out today via Regal House Publishing.

Cynthia Reeves on the web: cynthiareeveswriter.com