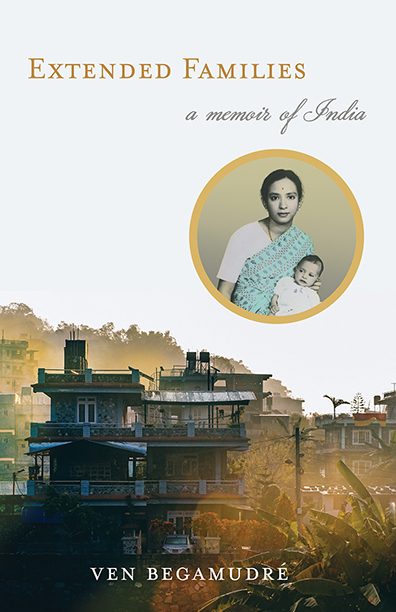

“Extended Families” from a new memoir by Ven Begamudré (fiction, ’99)

“Extended Families” is an Excerpt from Ven Begamudré’s memoir, EXTENDED FAMILIES: A MEMOIR OF INDIA.

“Extended Families” is an Excerpt from Ven Begamudré’s memoir, EXTENDED FAMILIES: A MEMOIR OF INDIA.

Somewhere in the U.S., a young man lives far from his family. True, he lives with his immediate family–his wife and child–but he often thinks of his larger, extended family: people he’s had no contact with for years.

His father was the youngest son of an Indian engineer, his mother the daughter of a Japanese soldier killed in the war. Their marriage was not arranged. They met in Yokohama while the father was in the Indian merchant marine. He used his earnings to purchase a flat in Bombay that he never got to live in. Now he accepted a transfer to London, a management position, then lost his job due to circumstances beyond his control. Their first child died. The second survived.

The merchant mariner grew poor. He returned to India only once, when his own father lay dying.

His wife and son lived in Osaka, Japan, with what remained of her own family. Her husband returned to sea but never admitted hardship until forced to seek help from his favourite brother: to adopt the boy should the need arise.

There proved no such need. The mariner’s reputation as a man who knew ships reached a Swiss bank. It hired him to approve the plans of ships it financed. Since most of these were built in the Far East, his knowledge of Japanese and of the Japanese proved useful. His wife and son left Osaka. Even as the boy finished primary school, his father became a vice-president.

The mother kept house in Geneva; the boy attended a polytechnique. The father drove a Mercedes Benz yet rarely entertained. The mother wouldn’t have known what to say. Chocolates and watches, yes, but Geneva was famous for other things: a lake, a lagoon, a fountain. Swans.

No one in the father’s extended family asked the boy, “Are you happy?” He was part Indian, part Japanese, born in London, raised in uncertainty. He could no more play the banker’s son than his mother could play the banker’s wife. It was said he took refuge in drugs, but those who claimed such things were the members of this extended family who were prone to passing judgment.

His father sent him to a private college in the U.S. It expelled him. By now his father was himself dying. Not of old age; he was fifty-one. He was dying of cancer, but it was his heart that failed him. One day he stopped at a pharmacy for his medicine. The last words he heard were French: “Calmez-vous.” Not even, “Calme-toi.”

What of the boy: the young man? He blamed everyone except himself. To stop him from squandering his father’s wealth, his mother called on the uncle, her husband’s favourite brother. The uncle issued orders. The young man rebelled. At last, it was said, he entered a clinic to seek help. Everyone congratulated the uncle. He congratulated himself.

While at the clinic, the young man made a friend. She too was from a wealthy family. Greek, it was said. She too was misunderstood, and neither had close friends. He didn’t marry her, though. He married someone else, an American. They live far from the family that never thought to ask, “Are you happy?” While playing with his child, he often thinks of the family he once had.

* * *

Somewhere in Switzerland, a woman lives alone. Over a decade has passed since her husband’s ashes were immersed in Lake Geneva. During afternoon walks, she ignores the banks on the opposite quay. Barely glances at the floral clock. Near the fountain in the lagoon, she loses track of time. If asked, she says, “I like to think . . . my husband swims with the swans.” Few people ask. It embarrasses them: her uncertain English, Berlitz French, the unforgiving Japanese.