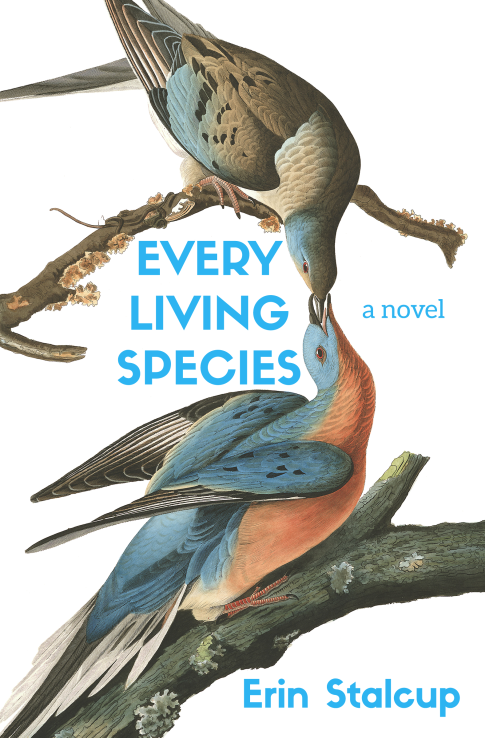

An Excerpt from Every Living Species by Erin Stalcup (fiction, ’04)

Read an excerpt from Every Living Species, a novel by Erin Stalcup (fiction, ’04), available now through Gold Wake Press:

Read an excerpt from Every Living Species, a novel by Erin Stalcup (fiction, ’04), available now through Gold Wake Press:

from Every Living Species:

the northern tip of Manhattan, the sixty-six acres of Fort Tryon Park had been transformed into The Aviary. Climate zones were built to house twelve of every living species of bird on earth—Polar, Desert, Coastal, and three kinds of forest: Deciduous, Coniferous, Rain. To launch this museum, Cabela’s and Canon teamed up to host the Birds of the World Timed Birding Contest. One thousand pairs of birders would be the first to see The Aviary, and would compete: three days to identify as many species as possible, and on the fourth day ten million dollars would be awarded to the first-place pair. Each of the 250 sovereign nations had sponsored a team; the United States sponsored fifty indigenous teams; there were fifty indigenous teams representing the rest of the globe; the ACLU sponsored fifty Visibility Teams made up of underrepresented individuals; Amnesty International sponsored one hundred Peace Teams combining members from nations that had experienced recent or historical conflict; and there were five hundred pairs of paying customers.

This is what the birds would see if they ventured beyond the climate where they were

most comfortable, though they didn’t have language to say it: a glare of barren white, a swath of verdant green, scarlet desert sand, a lucent lake, a sea.  Alpine lichen abutted arctic ice, cacti stood adjacent to grassland, and all three kinds of forest flanked each other—leafed, needled, jungle—just like on the planet, but compressed. No walls separated environments, so contestants would walk under a canopy of branches and arrive in the tropics, moisture streaming from unseen machines in the sky. Nearby, mechanisms masked as stones circulated frigid air in the late New York summer, kept ice intact for a small space, and contraptions released snow every hour on the hour. Chilled air drifted away at the edges, transitioned to a woodland of spruces, firs, and pines. Farther along contestants could stand between a miniature ocean and a freshwater lake, see two shores at once. Sand led to the arid zone, where an apparatus baked the liquid out of the air. The tightest knit of chain link surrounded the park, an optical-fiber canopy stretched overhead.

Alpine lichen abutted arctic ice, cacti stood adjacent to grassland, and all three kinds of forest flanked each other—leafed, needled, jungle—just like on the planet, but compressed. No walls separated environments, so contestants would walk under a canopy of branches and arrive in the tropics, moisture streaming from unseen machines in the sky. Nearby, mechanisms masked as stones circulated frigid air in the late New York summer, kept ice intact for a small space, and contraptions released snow every hour on the hour. Chilled air drifted away at the edges, transitioned to a woodland of spruces, firs, and pines. Farther along contestants could stand between a miniature ocean and a freshwater lake, see two shores at once. Sand led to the arid zone, where an apparatus baked the liquid out of the air. The tightest knit of chain link surrounded the park, an optical-fiber canopy stretched overhead.

Inwood Hill Park had been converted to a campground for contestants, 196 acres of original forest north of The Aviary, the only place in the city you could still see trees that had been alive for over a century. Many New Yorkers thought all the parks were what was left of prehistoric forest, and skyscrapers had grown around what had been preserved, but in fact most of Manhattan Island had been flat as a field. Fort Tryon Park had been rocky and thin-soiled until nearly one hundred years before when Frederick Law Olmsted brought in fertile dirt, planted oaks, moved boulders, scooped out promenades. Olmsted positioned every stone in Central Park, situated each tree, dug and filled the lake, then duplicated his work in Fort Tryon. The architects for the Canon and Cabela’s Birds of the World Timed Birding Contest pulled out Olmsted’s maples, replaced them with palms and piñons.

The masses were gathering, preparing to compete to see who could witness the most beauty, bringing their cravings and fancies and fears, drawn as if the colored lines of subway tracks on maps stretched across the globe to wrap people and pull them close—and New York City was planning a party to greet the beginning of the end of the world.

American Ballet Theatre would perform a double-bill of Swan Lake and Firebird. The Metropolitan Opera would present Die Vogel. The Museum of Natural History would have an exhibit called Extinction: one wing holding paintings, photos, and stuffed specimens of every extinct bird, so contestants could come as close as possible to seeing every species that ever existed; a wing featuring taxidermy of other extinct animals; a wing of artifacts and relics of extinct peoples and languages; and of course dinosaurs. Revive & Restore sponsored an exhibit called De-Extinct, where you could see live species that had been returned, but weren’t quite yet ready for release into the wild. The Cloisters showcased medieval conceptions of birds, tapestries and illuminated manuscripts. Art galleries hosted Brandon Ballengee’s erasures of Audubon’s prints, Frederick Murphy’s and Alicia Kanade’s photographs of viruses that could decimate the human population, and photographs from National Geographic entitled What Still Remains. Banksy’s retirement project would be to graffiti a bird a day in an obscure location during the month of September so some could search outside of the park, for free, and the resuscitated piano bar Rose’s Turn would host an all-bird-name drag show, emceed by Tequila Mockingbird. Most bars would feature bird-themed cocktail specials, some restaurants would feature fowl-free menus for the duration, while others would run ostrich and squab and quail and pheasant and turkey specials beyond the regular chicken. “Come see the spectacle!” the papers all proclaimed. “Celebrate obliteration in all five boroughs.”

BIO: Erin Stalcup is the author of the story collection, And Yet It Moves (Indiana University Press 2016) and the novel, Every Living Species (Gold Wake Press 2017). Her fiction has appeared in The Kenyon Review, Kenyon Review Online, The Sun, and elsewhere, and her creative nonfiction about her teaching experiences was listed as a Notable Essays in Best American Essays 2016. After earning her MFA from Warren Wilson Program for writers, she served as the Joan Beebe Teaching Fellow. Erin has also taught in community colleges, universities, and prisons in New York City, North Carolina, and Texas, and she now teaches fiction writing at her alma mater, Northern Arizona University, in her hometown of Flagstaff. Erin co-founded and co-edits Waxwing: www.waxwingmag.org. You can read more of her work at www.erinstalcup.com.