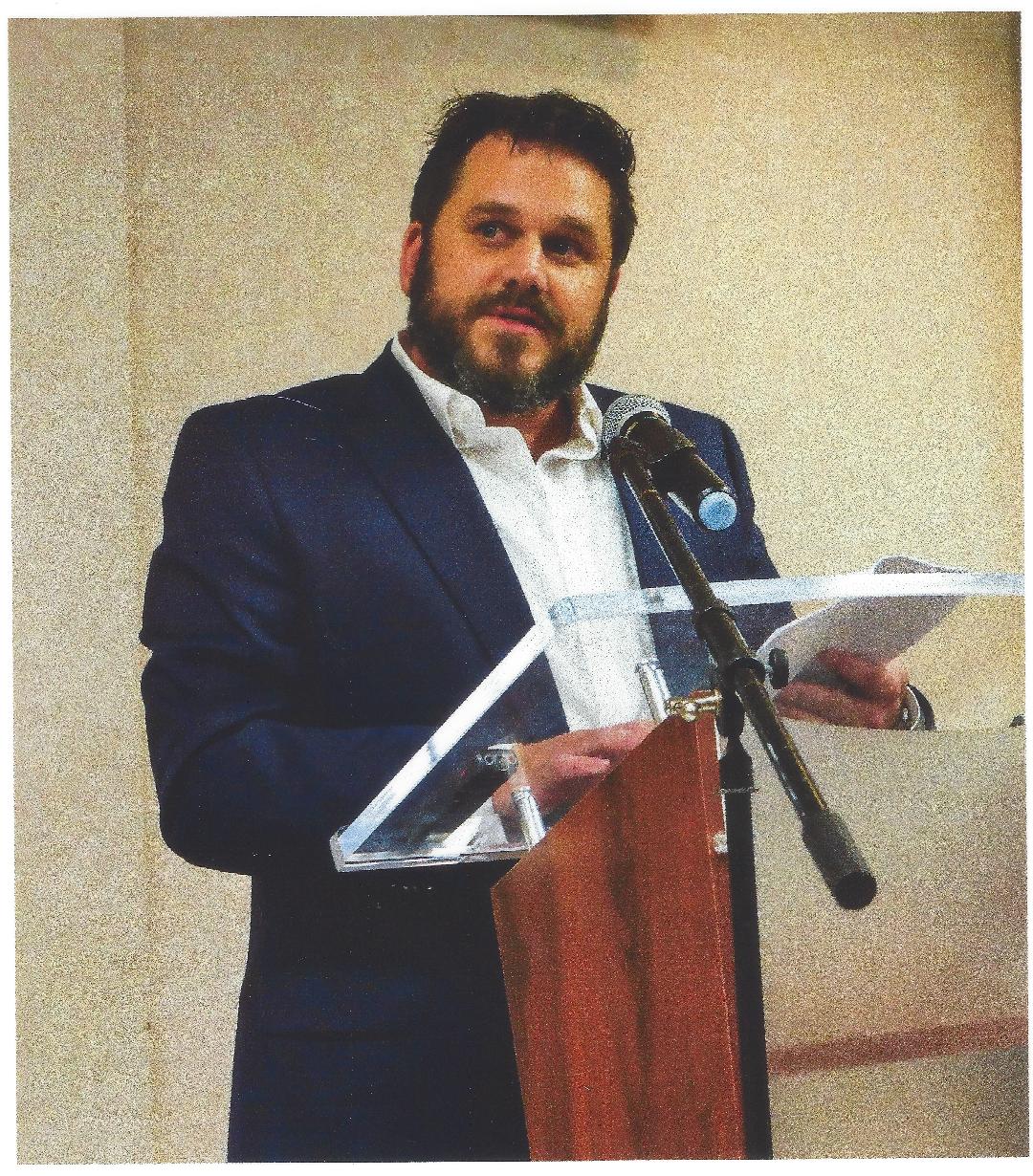

January 2018 Graduation Remarks by Dean Bakopoulos

Photo by Joseph Nieves

Good afternoon, graduates, and welcome to their beloved spouses, partners, children, parents, poet pals, and friends. As much as all the writers in the room, you, the dear friends and loved ones of our students, make this unique, weird, program possible. If you’re here today, you have done one of the most difficult and loving acts you can do for someone: you’ve supported them as they pursued a passion that you may not fully understand. Thank you for that.

Several years ago, at a fairly dull conference in some forgettable city, I was seated with some of my writing pals, sipping drinks in a hotel bar. There was one other man in the bar, dressed in casual business wear, and he kept looking at our table. He could hear us erupting with laughter, and he could see we had the good-natured, affectionate slouches of old friends gathered after a long day.

He wasn’t dreadfully drunk, but he was on his way there, when he pulled up a chair at our table and said, “So, this some kind of work thing? What do y’all do?”

I finally confessed: “We’re writers,” I said. “We write books.”

“Huh,” he said. “Well, I hate writing…not much of a reader either.”

We greeted this with silence, with hopes the man might leave us alone, so we might go back to those riveting jokes we tell each other that nobody else understands—I’m gonna rewrite that poem in spondees, hahahaha, or what would free indirect speech even look like in first person, lol.

But this particular party crasher, a salesman by trade, regrouped, grinned again, and said:

“Well, what about hobbies?” he said. “What do you guys do for fun?”

Another awkward silence at the table.

“Uh,” we said. “Read and write?”

“Oh for Pete’s Sake,” the man said, and went off in search of a livelier crowd.

Most writers don’t have a lot of hobbies. We have engaging distractions or occasional obsessions that feed our work, but no real hobbies. Sometimes, when small-talking strangers ask me about my hobbies, I lie.

I like hiking, I say, though I don’t admit I mainly like hiking because I enjoy walking around thinking about whatever it is I’m trying to write. I do like dancing, though in truth I only like to dance when I’m surrounded by other writers.

You get the idea.

In the weeks ahead, some well-meaning people will tell you that now that you have an MFA, they can’t wait for you to win the Pulitzer or land on the bestseller list.

These are things people usually say because they love you and think you are capable of anything.

But it is a curious question that people seem to ask emerging writers of all ages when they leave a writing program.

“What’s next?”

If someone you know comes back from a golf weekend in Lake Tahoe, you don’t ask them, upon their return, if they’re joining the PGA next week. When a friend returns from Cancun and shows you vacation photos, you don’t ask her if she plans to become a professional parasailer.

We just understand that these people spend time and resources and energy doing something they love, without expectation.

But artists who invest in themselves as artists are almost always asked, “What’s next? What will you do with that?”

The truth is you have no idea what’s next. At Warren Wilson, you made the brave and probably inconvenient decision to dedicate yourself wholly to your art for no reason other than you love to do it.

Or, maybe, it was more than love; maybe, as I talked about in my opening lecture this year, it was survival. In fact, if you really want to shut down the “what next” questions about your writing career, when someone says “So what can you do with thatdegree?” just say, “Baby, I can come alive.”

For the past few years, we’ve seen you come alive as you’ve put this creative work on the proverbial front burner. But the truth is, we all have times in our life where what we love to do is not on the front burner. It’s not even on the back burner. It’s not even in the kitchen with you and the kitchen you’re in is not even a cool kitchen. It has crappy light and a low ceiling and busted fridge and your credit card will be maxed out. I have no doubt in my mind that all of you will be in this kitchen sometime in the years ahead, with nothing on the burners.

And when that happens, I hope you will remember that you can love this life even when you can’t live it seven days a week. You can love this life even when there’s no mentor waiting at the other end of your outbox every three weeks.

Why? Because all the work you’ve done these past few years will never disappear. The manuscripts you’ve written will evolve and take new shapes and the books you’ve read and re-read will evolve and offer you new meanings and your way of being in the world will constantly evolve as this happens. That will never end.

This evolution will happen in your most secret, interior places; this will happen in your darkest, strangest times, BECAUSE what you’ve done in the past few years is an incredible and revolutionary accomplishment in our current world: you’ve transformed and celebrated and respected your inner life.

If there were any doubt that you could call yourself a writer before this program, let it leave you today. You have survived the nerdiest, most intense, hardest working creative writing program on Earth. And you’ve given us so much–your struggles in the program and the concerns you’ve raised have also helped us grow. We, as a community of writers, we, as your mentors, have benefitted not just from your triumphs but also from your moments of uncertainty, anger, and struggle. I believe that we have benefitted from seeing the real you, your true self. As I like to say to my students, you can’t hide in a packet.

One of the most pernicious and insidious elements of contemporary American culture is that it has the ability to constantly give you new reasons to hate yourself. To hate who you are or how you look or what you lack or where you’re from or how you feel and what you say.

But right now, in this moment, I hope that you love yourself. Love yourself for enduring the struggles and challenges. Love yourself for considering yourself worthy to study literature and to create your own. Love yourself for surrounding yourself with the people who build you up and not the ones who tear you down. Love yourself for your radical creativity.

Family and friends, we return these writers to you today as changed beings.

Is this hyperbolic?

I don’t think so. They’ve changed. They don’t love you any less, but they do love themselves more. And by loving themselves more they will also love you more wholly and expansively in the years ahead and in doing so love the world more and transform it.

Graduates, I truly hope you leave here today loving yourself more than you did two or three or four years ago. You may occasionally doubt the work, or hate the slow pace of your “career,” or struggle with systems intractable and ignorant.

But when those feelings of self-loathing or panic or doubt creep in, I want you to remember this moment, this day, when you love yourself because you were true to your calling.

I mean it. I invite you, come back to this very moment. Forget everything else. Focus on the love you now have for yourself, right here, in this space, among your people. Focus on the love you have for literature, and the ways it saves you, and for others on that same journey. Focus on my unkempt beard, if you must. But do whatever you need to do to remember this moment of self-love and creative power and tap into it daily.

This feeling, these mountains, this community of writers, right now is all real and it’s here in front of you, but later, you can visit it within yourself whenever you want. It’s not going anywhere.

But you are.

May the world welcome your new self with an open heart.