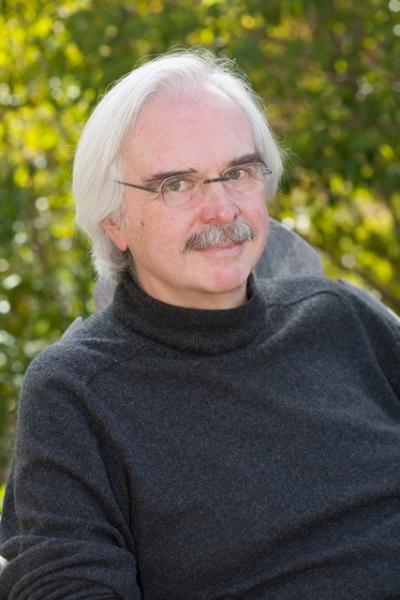

2019 fiction alum Candace Walsh recently interviewed fiction faculty member Lan Samantha Chang for Craft Literary. Read an excerpt of their conversation below:

CW: What was it like to write an homage to The Brothers Karamazov? I noticed that women characters had a more well-developed presence in The Family Chao. And the perspectives of family members of a Chinese-American family who own a Chinese restaurant in Wisconsin allow readers to notice, firsthand, micro- and macroaggressions white individuals and mass media inflict on the Chaos and other Asian characters.

LSC: I did consult Margot Livesey’s essay on homages in The Hidden Machinery: Essays on Writing. She shared that while writing The Flight of Gemma Hardy, an homage to Jane Eyre, she had to put Jane Eyre aside for years. One of the first serious steps I took was to reread The Brothers Karamazov and take notes on the entire novel, but then I had to put it (and the notes) aside. It’s such a tremendous book; it could have scared me off from working on my own novel for years. In that vacuum I was able to gather the confidence to try to do what I was interested in doing. Pretty quickly, after I started drafting, I realized my book was going to be its own thing, get its own energy from itself. For one, the characters of Katherine, Brenda, and Alice each developed her own concerns that set them apart from their Dostoyevskian prototypes. The setting, subject matter, and characters were also obviously entirely different: an immigrant, restaurant family in the Midwest. As I became interested in their concerns as a family, I was able to bring my project into its own.

Read this interview in its entirety here: https://www.craftliterary.com/2022/02/01/interview-lan-samantha-chang/