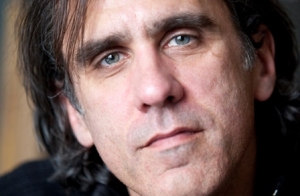

An interview with Faculty member Robert Boswell on, among other topics, his new book, Tumbledown, appears online on the TIn House blog:

Robert Boswell is a patient man. The facts surrounding this interview support this claim.

Our conversation began in Telluride, where he and his wife, the writer Antonya Nelson, have a home. This was a year ago and I should mention that our weekend together began with me flying into the wrong airport some 90 miles north of where he was waiting to pick me up. He stoically stayed up until a shuttle service dropped me off at his home around 1:00am. We spent the next few hours catching up and talking about Alice Munro.

Over the course of the ensuing weekend we must have watched 100 hours of baseball. That might be an exaggeration but it was the playoffs and I don’t think we missed an at-bat. It makes sense that Boswell would love our nation’s pastime; a four-hour, one-run pitching duel is the perfect requiescence for a man who often writes over fifty drafts of a novel. The same sort of patience that goes into his writing can be seen when you are heading home from the bar after the game and you encounter an enormous bear foraging in a nearby trashcan. “We should probably walk a bit faster,” he said.” “But not too fast. Now getting back to Wise Blood.”

And so a year has passed and the baseball playoffs are about to start again (without Boswell’s beloved Astros) and the bears of Telluride are hoping for another autumn book recommendation. The season has brought with it a bit of a relief, for after ten years we have finally gotten another Robert Boswell novel to immerse ourselves in.