“All My Pretty Hates: Reconsidering Charles Baudelaire,” an essay and winter residency lecture by faculty member Daisy Fried, appears online at Poetry.

I’m writing this in Paris, so, from my many poetic aversions (“all my pretty hates,” to quote Dorothy Parker): Charles Baudelaire, oozing with decay, pestilence, and death. Baudelaire, tireless invoker of muses, classical figures, goddesses, personifications: O Nature!…Cybele!…

Sisyphe … O muse de mon coeur! Baudelaire, who makes an old perfume bottle an invocation of the soul wherein

A thousand thoughts were sleeping, deathly chrysalids,

trembling gently in the heavy darkness,

which now unfold their wings and take flight,

tinged with azure, glazed with pink, shot with gold*

— From The Phial

Anyone ever counted how many times “azure” shows up in Les Fleurs du Mal?

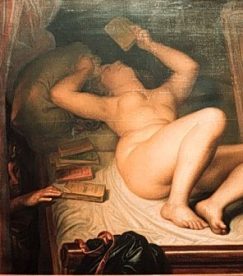

When she had sucked all the marrow from my bones

And I languidly turned to her

To give back an amorous kiss, I saw no more.

She seemed a gluey wine-skin full of pus.

— The Vampire’s Metamorphosis

I’m not one to criticize poems about blowjobs but Really, Charles? My fourteen-year-old self might have been impressed. Ew, gross. Then again, shouldn’t one be aware of not reading through one’s fourteen-year-old eyes? After all, he and Poe invented poetic goth. It’s not Baudelaire’s fault his modern-day followers are goofballs. And not their fault I’m a boring middle-aged American...[Keep Reading]…

You can see clips of other Warren Wilson MFA lectures at Youtube.com/FriendsofWriters, or purchase recordings at the Audio Store.

(2013, Graywolf Press).