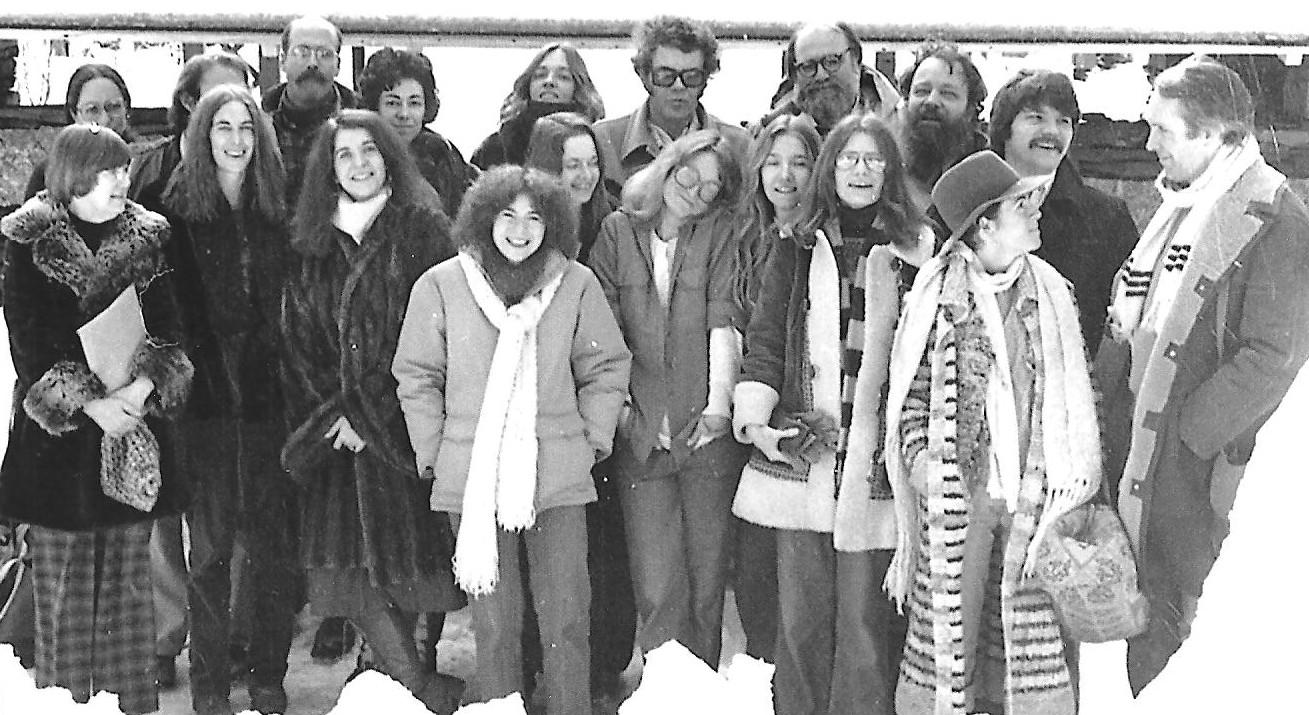

Remembering Goddard MFA Faculty Member Lisel Mueller

Poet and translator Lisel Mueller was a member of the original MFA Program for Writers faculty at Goddard College. Her collections of poetry include The Private Life, which was the 1975 Lamont Poetry Selection; Second Language (1986); The Need to Hold Still (1980), which received the National Book Award; Learning to Play by Ear (1990); and Alive Together: New & Selected Poems (1996), which won the Pulitzer Prize. Her other awards and honors include the Carl Sandburg Award, the Helen Bullis Award, the Ruth Lilly Prize, and a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. She also published translations, including Circe’s Mountain by Marie Luise Kaschnitz (1990).

Poet and translator Lisel Mueller was a member of the original MFA Program for Writers faculty at Goddard College. Her collections of poetry include The Private Life, which was the 1975 Lamont Poetry Selection; Second Language (1986); The Need to Hold Still (1980), which received the National Book Award; Learning to Play by Ear (1990); and Alive Together: New & Selected Poems (1996), which won the Pulitzer Prize. Her other awards and honors include the Carl Sandburg Award, the Helen Bullis Award, the Ruth Lilly Prize, and a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. She also published translations, including Circe’s Mountain by Marie Luise Kaschnitz (1990).

Over the past two decades, parents of young children have been able to pursue their MFA at Warren Wilson with the support of a scholarship established in Lisel Mueller’s honor by MFA alumna Linda Nemec Foster. About her friend and mentor, Linda says:

I first met Lisel Mueller in July of 1977 when I began my tenure in the first low-residency MFA Program in Creative Writing founded by Ellen Bryant Voigt at Goddard College in Vermont. (As everyone knows, that ground-breaking program moved to Warren Wilson College in the early 1980’s). During that first residency, I wanted to work with Lisel because of the powerful themes of mythology, folklore, and fairy tale motifs that informed so many of her remarkable poems. I was also fascinated with these themes and working on a long sequence of poems inspired by the Russian witch Baba Yaga. Lisel was the perfect advisor to guide my first semester as I wrote poems about Slavic mythology and read numerous books on fairy tales and scholarly research that revealed their historical, psychological, and cultural underpinnings. During my critical paper semester, I was fortunate to work with Lisel again as I focused on Rainer Maria Rilke and his seminal book, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. Who better to guide my research and critical analysis than this native of Hamburg with her understanding of Rilke’s language, psyche, and creative artistry? The focus of these two semesters were totally different, of course, but one thing was constant: Lisel’s complete dedication to her job as a teacher/mentor and to my job as her student. Wisdom, patience, understanding, honesty. These were Lisel’s traits, but she also had another remarkable gift—to nurture her student’s own poetic voice and not impose her particular style or mindset. I was so fortunate to have her guidance as I started my career as a poet.

These are my memories of those MFA years, but I’d also like to share some thoughts about my relationship with Lisel after I graduated from Goddard in 1979. Over the years, our relationship continued to evolve and grow: Lisel became more than a teacher or mentor—she became a close and dear friend, like a member of our family. We developed a wonderful correspondence, sharing new poems and ideas about the writing life and our personal lives. My husband and I, with our son and daughter, would frequently visit Lisel and her husband Paul in their home in Lake Forest, Illinois. Such a wonderful house with a large yard, nestled on the edge of prairie grasses. We spent my first Mother’s Day with them in 1980 when my son Brian was only six months old. And when Lisel won the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry for her book Alive Together in April of 1997, it just so happened (miraculous, really) my daughter Ellen and I were visiting her and Paul for several days. What an experience to share that heady, celebratory time with her.

In between those years and ever since, I’ve collected a lifetime of memories of a woman who was truly extraordinary in every sense of the word: from her stunning poetry to her generous teaching; from her unique history to her amazing life. And, above all, hers was one of the most genuine hearts I’ve ever known. My good and dear Lisel.

Linda’s colleague Heather McHugh adds:

Too wise to be merely judgmental, Lisel saw things from a wider angle than most. She was of considerate character, very calm and kindly. Study a language on poetic grounds and you get releases on reason; study two or more and you get holds on sway. Lisel’s translations of Marie Luise Kaschnitz give us the best of all worlds. Our breaths and breathlessness may all be lost, but many souls are saved by measures such as these:

Alumna (Goddard poetry ’80) and Warren Wilson MFA faculty member Joan Aleshire recalls beginning her studies with Lisel:

At our first supervisor-student meeting at Goddard, she asked me, as part of our semester’s work, to send her letters about the “life of the mind”: anything that informed my thinking and inspired my nascent poems, whether poetry, music, films, dance, prose — which made me feel that someone took what I might say seriously, and also that a new world was opening in all its possibilities. More than any comment on a poem, that was an enormous gift.

Finally, from the archives, Lisel’s Introductory Statement for her prospective students:

I think of myself as flexible, but some students have discovered a stubborn streak in me…I am quite flexible when it comes to the reading list we design at the residency. I believe that the most fruitful and joyous reading comes when the imagination is excited, and that excitement is often brought about when a book sends out branches, suggesting other books… I’m stubborn about expecting students to revise, sometimes repeatedly, if I feel a poem has not yet found the language or overall structural design for which, however dimly, it seems destined. I think of revision not merely as a process of refining, but unearthing–discovering what the poem really wants to be. I consider it my function to help you in that discovery by reading your work closely, and with as much empathy and insight as I can bring to it.