2014 poetry graduate Daye Phillippo was recently interviewed for Slant Books. Read an excerpt below:

Poets have reported various triggers for poems—sounds, scents, etc. What triggers a poem for you?

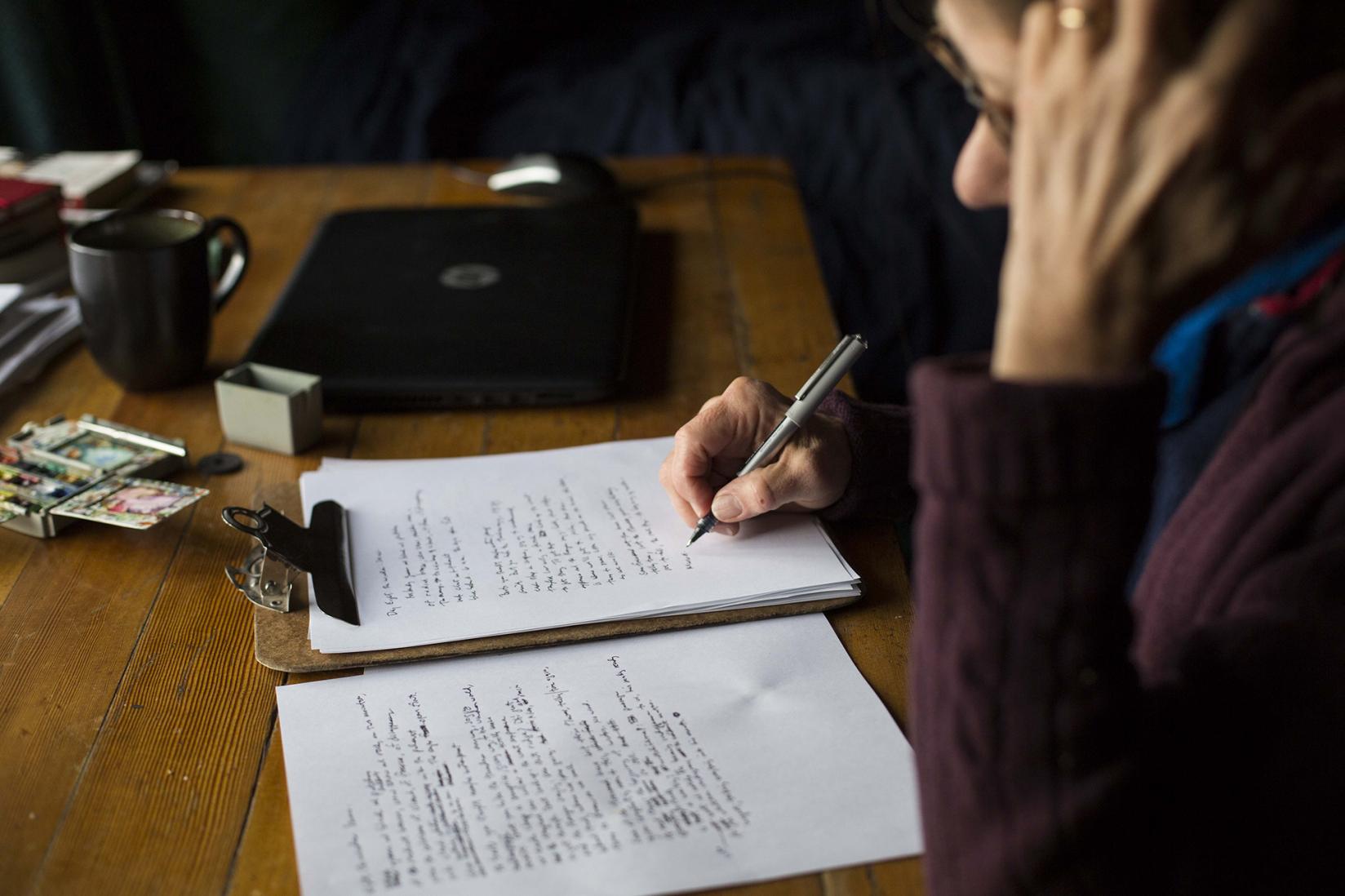

For me, a poem almost always begins with an image, something that catches my eye—a weird tree, a hawk swooping low across the hood of my car, something out of the ordinary. I jot it in an image journal, or just bring the image straight to a notebook or to the computer, and begin describing. It’s by getting as deeply and accurately as possible into an image through description that other things begin to open up for me, discoveries are made, and things I had no idea I’d be writing about begin to show up. That doesn’t always happen, of course, but it’s like a thunderhead rolling in when it does. It’s what keeps me coming back.

For instance, with my poem “Fledgling,” I was weeding in the garden one day when I noticed a robin fledging on the ground by a tomato cage and I realized that that little bird was out of its nest, maybe for the first time, learning to fly. What an exciting time, the beginning of everything new for this little bird.

I left my weeding and came in the house to begin describing what I’d just seen. Suddenly I found myself writing about something that had happened to me way back when I was at what could be called the “fledgling stage” of my own life. I’d had no idea the poem would turn that way when I first started writing. I was just trying to document the cool experience of seeing that little speckled fledgling up close.

Personal discovery is part of it for you, then. Anything else?

Oh, yes! Let me quote Thomas Merton here since I believe he explained this part of the writing process for a person of faith in such a beautiful way:

“The earliest [church] fathers knew that all things, as such, are symbolic by their very being and nature, and all talk of something beyond themselves. Their meaning is not something we impose upon them, but a mystery which we can discover in them, if we have the eyes to look with.” (Selected Poems of Thomas Merton)

Isn’t that lovely? That’s my prayer now—Lord, give me the eyes to look with!

During undergrad at Purdue, I took dendrology (the study of trees), tree physiology, and several urban forestry classes. When people asked why, as a creative writer, I wanted to study trees, I told them that I studied trees not only in the hope of writing better poems, but also in hope of better understanding the mind of their Creator. As a person of faith, spiritual insight is something I’m hoping for every time I write.

Read the interview in its entirety here: https://slantbooks.com/2020/08/03/the-sky-as-a-body-of-water-qa-with-daye-phillippo/