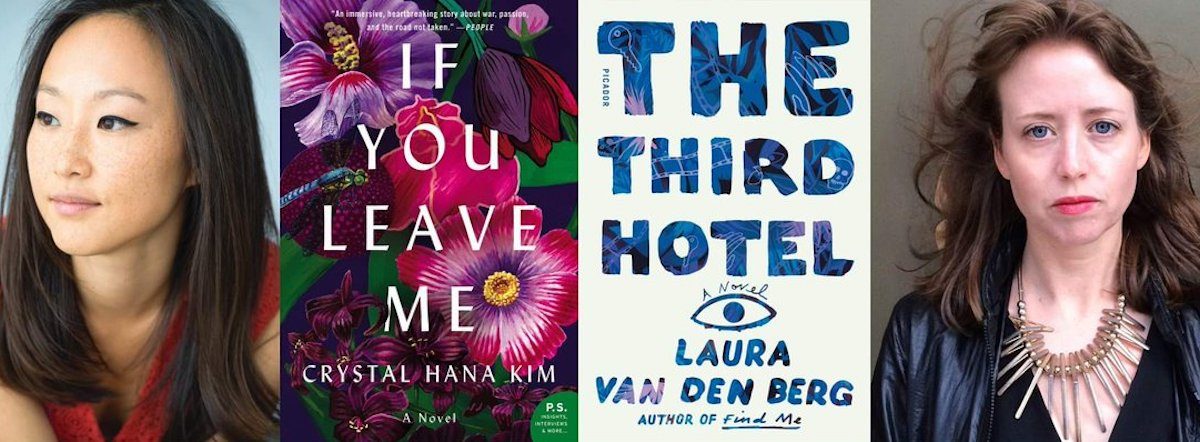

After reading and loving Crystal Hana Kim’s debut novel, If You Leave Me, it was a great joy to team up with her for a joint paperback celebration. This conversation took place at the lovely Books Are Magic in early September. We talked about what it feels like to be a year out from publication, vulnerability, voice, research, and writing the next book.

–Laura van den Berg

*

Crystal Hana Kim: I’m really excited to be here with you, and I’m excited that we can celebrate together. I also want to say that I’m selfishly thrilled about this event because I want to learn from you. You’re so prolific, and we’re at different stages in our writing careers. What would you like to talk about first?

Laura van den Berg: Since this is a paperback celebration, this event is coming at a different moment in the life of these books. What has the last year been like for you? What have you learned? What has surprised you? What challenged you?

CHK: Before If You Leave Me, I had not published much—I went to grad school at Columbia, but I moved to Chicago for four years right afterwards, and I was outside of my literary community. That distance allowed me to sink into the world of Haemi and Kyunghwan and Jisoo. But at the same time, since I hadn’t published anything except for one short story that actually was just an earlier iteration of a chapter in my book, I wasn’t used to the publishing world. I didn’t realize how vulnerable I would feel. Even though my book is set in 1950s to late 1960s Korea, and it’s not autobiographical, I felt so vulnerable this past year. This strange writerly anxiety came over me. Do you ever feel like that, before a book comes out?

LVDB: All the time!

CHK: I was really nervous, as if everyone would be able to pinpoint all of my secret obsessions and fears. But after you get over the initial fear, it’s an incredible experience. It’s been particularly amazing hearing from different readers—from Korean Americans, mothers who told me that the way that I depicted postpartum depression stayed with them, or war veterans.

LVDB: I think it is also a particular thing for novels. I think publishing any book can be anxiety-inducing. But with short stories, people very often publish them in magazines along the way and so other people have seen them and found them legible. With novels, a part of my worries is: will this make sense to anyone who’s not me? Did I just have a weird dream and write it down continually for three years? And a novel is a very private thing for a long time, so I think also that when it finally goes out into the world it can feel like a bit of a loss.

[… continue reading their conversation at Literary Hub.]