An excerpt from “Facts That Turn Out to Be Fiction: Ann Cummins and Sarah Stone on Writing, Landscape, and Family,” published at The Millions:

An excerpt from “Facts That Turn Out to Be Fiction: Ann Cummins and Sarah Stone on Writing, Landscape, and Family,” published at The Millions:

Facts That Turn Out to Be Fiction

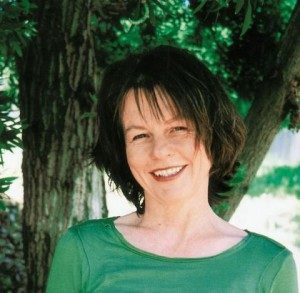

We met in 2002, when we were teaching at Pima Writers Workshop. Later that summer, we were fellows, and roommates, at Bread Loaf Writers Conference. For nearly a decade and a half, we’ve been friends and in the same writers’ group, reading each other’s stories, plays, novels, and nonfiction, including Ann’s novel Yellowcake, the family memoir she’s working on, and Sarah’s new novel, Hungry Ghost Theater.

Our conversations usually take place as we walk by the San Francisco Bay, discussing our families and lives, but this time we sat down in Sarah’s living room with a couple of tape recorders and a pile of pastries Ann had brought over. Our initial conversation was full of those moments between old friends where you say about a third of a sentence, see full comprehension in the other person, and immediately tack to a new thought. So we followed up and added to the conversation via email.

Ann Cummins: Your characters in Hungry Ghost Theater have the authenticity and intimate appeal of people struggling with real-life issues. I mean, the family at the center of this book pulses with believable complexity. Did you draw from your own family as prototypes for your characters?

Sarah Stone: Like the family in the book, members of my own family have wrestled with mental illness, addiction, and alcohol, though in very different ways than these characters. I love to read books that come from the poetic or memoiristic urge to write down what happened, to make sense of it. But I feel an internal prohibition about doing that. Also, I’m interested in making up stories. I can’t help it. If I say to myself, I would like to try to tell the truth about this, I just start turning it into a story. In my life I feel—and this may be a lie I tell myself—that I’m truthful to a fault, truthful to the point of potentially putting people’s backs up.

[…continue reading here]

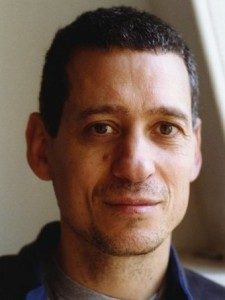

An excerpt from the poem “Transept” by C. Dale Young, published at Scoundrel Time:

An excerpt from the poem “Transept” by C. Dale Young, published at Scoundrel Time: