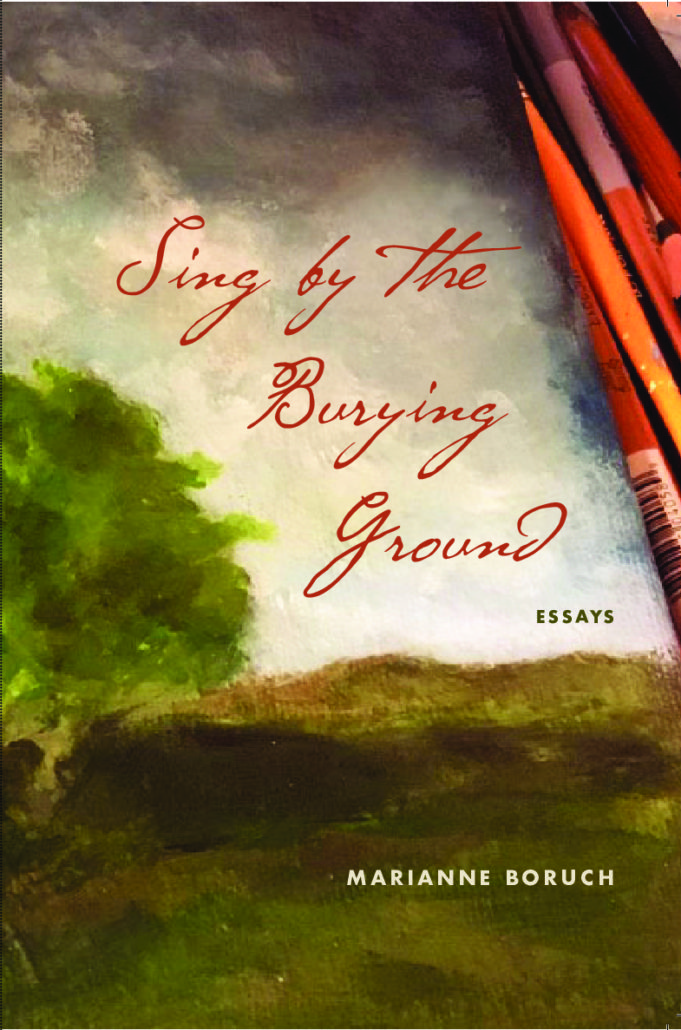

Sing by the Burying Ground by Marianne Boruch

Poetry faculty member Marianne Boruch’s essay collection, Sing by the Burying Ground, was released on March 15th by Northwestern University Press. In her foreword, Marianne writes, “These oddly eked-out pieces are uncertain experiments and honest attempts to understand what I consider the most mysterious and addictive literary genre we have.”

Read the essay, “Shirt,” below:

SHIRT

One word. But it depends on the word, I suppose.

Chicago, circa 1962, at my parish school, an army of boomer-kids, about fifty of us, shuffled in from lunch and recess to find the word shit scribbled on the blackboard in Sister Mary Generose’s seventh grade class. Hastily written, just that word, no exclamation point, not embedded in some snarky phrase for personal assault, zip. It was a pure abstraction. If faced today, not much more than a shrug, an eye roll, or a nod of amused agreement would come of it. But in the early 1960s, that particular word in chalk was the gauntlet thrown down in a battle of dire consequence, a flare in the night sky, an unthinkable instance of outrageous nerve, especially in Catholic school.

Our teacher rushed up to erase it and, threatening Armageddon if we so much as cleared our throats, sped off to confer with her compatriots of wimple and full black habit. What happened next: a spelling test from nowhere and she read aloud what we were to eke out—chemistry, nasturtium, ridiculous, hieroglyphics. Next came shirt. Just shirt, clearly a “baby word,” we full-of-ourselves 7th graders sneered later, getting the drift: a trap our teachers had set to bring down the culprit with a similar-sounding something that seemed written in a similar hand. (Though honestly, who knew, wiped from the board so fast?)

In any case and therefore: rock-bottom proof.

Aha! they must have said and most certainly thought, that small gaggle of nuns riffling pointedly through our tests. See the way he makes his t, his s? Edward K–! What a surprise, the infamous bad boy with his sharp tongue and vast indifference. Also: lock-jawed, steely-eyed, gorgeous, austere, his posture ramrod-straight. And was it really Edward who dashed off that word on the board? I think yes then no, but most of the time, who cares. My husband likes to imagine the oldest nun there as school rebel, slipped into dementia, loosening the bonds of eighty-nine years of inhibition.

What I remember has narrowed over the years to a glimpse, a flash, a doorway that the Roman god Janus must have guarded with his terrifying doubled face, one side looking back, the other far into the future. It was mythic and thrilling; I sat right by that door. Edward’s mother had been called to school. She was weeping in the hallway, ferociously fragile, making sad piercing noises between the two nuns meant to handle this atrocity. And Edward, defiant and beautiful, chin raised, eyes on some amazing lifetime to come stood near her, silently enduring the “case” against him. Expulsion. He was out, his course set. One word can turn the key.

Or, one stray image. Thus a claim I heard once about Joseph Conrad, that on shipboard briefly he’d seen a figure in a deckchair reading, then not reading at all. How the old man held his magazine, the way one leg lay casually over the other, a cigarette between forefinger and thumb, his tweed overcoat neatly folded beneath, etc. And so Victory, I was told, Conrad’s fourteenth novel, launched itself. True or not, this is exact: just a quick look. The time-stop power of pure attention. One is struck down, pinned, smitten.

What’s the standard phrase? I’ll never, ever forget…. In my case, so many ghostly bits hang on in me but among them that poor woman in collapse, the officious nuns panicked by a silly nick of profanity, the brilliant resistance in a boy framed and already sure that out there a world waited. Then, he was gone.

As for Victory, it became a part-time job to help keep us afloat. In my twenties, I read the novel to someone, a sizable section each day for the ancient woman who’d hired us to cook for her too, in the downstairs apartment of the old house my husband and I shared with her in Amherst, Massachusetts when I was in grad school. He and I took turns with the reading, quietly absorbing each other’s chapters on our off-days, to keep up.

I walked downstairs to another world. But I distinctly remember hearing Conrad in my own voice, mouthing his words, though I didn’t find—at least can’t recall now from those pages—the man who smoked and stared out to sea, who burrowed into that writer so deep that a whole book, a rich inner life to continue and cherish, came of it.