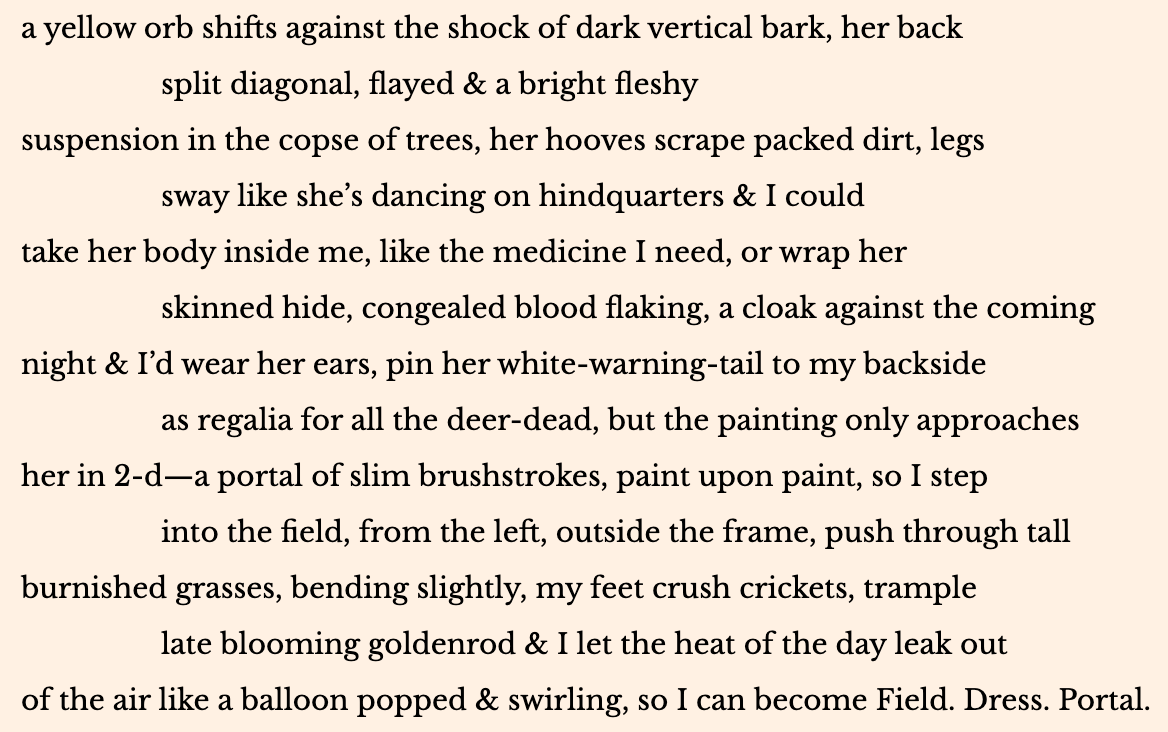

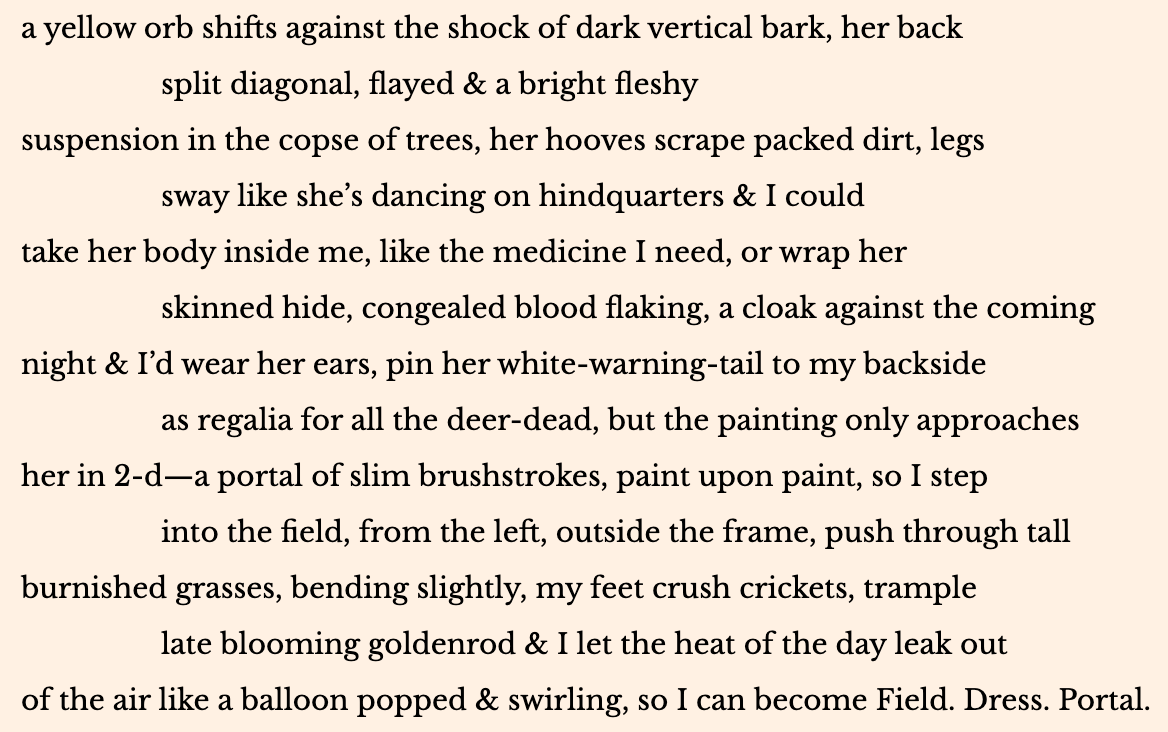

“Field Dress Portal,” a poem by poetry alum Sarah Audsley, was recently featured in the New England Review. Read an excerpt below:

Field Dress Portal

Read the rest of this poem here: https://www.nereview.com/volume-41-no-4-2020/field-dress-portal/

“Field Dress Portal,” a poem by poetry alum Sarah Audsley, was recently featured in the New England Review. Read an excerpt below:

Field Dress Portal

Read the rest of this poem here: https://www.nereview.com/volume-41-no-4-2020/field-dress-portal/

Glenis Redmond, a 2011 poetry alum, was recently featured in the Blue Nib Review. Read an excerpt of “Hang Man (Woman)” below:

Hang Man (Woman)

As kids, what did we know?

We drew the noose.

We thought it just a guessing game,

but mama’s mouth as scissors

told us otherwise.

Read the rest of this poem, as well as two others, here: https://thebluenib.com/three-poems-by-glenis-redmond/

2011 fiction alum Nathan Poole was recently featured in Shenandoah. Read an excerpt of “Now There Is Only You” below:

Now There Is Only You

he day before her son eloped, the rains came and the river increased. She recalls the immense, confused sound in the woods behind their home. All day, dense endless thunder. In the evening hailstones gathered in strings along the iron lip of the gutter.

By then she’d forgotten the romantic overtones—eloped—word for lovers. She hears it still. The palm-warmed pebble tossed against the upstairs window, the trestle descent—but not for her child, her boy. Autistic children do not run away with lovers, they just run off with themselves. What must it be like to have such a slack sense of home, or attachment? “Elopement,” as the clinicians say, a behavior half of all autistic children engage in. Another form of wandering, of withdrawing, from her, from her love, her need of him, which grew stronger only as he grew older and more independent of her, more willing to shrug her off—to shrug the world off too, water off a duck’s back.

▴ ▴ ▴

If her son had shoes on when he left that morning, the river took them. The river took everything but his bicycle helmet. The bright orange one, perhaps the only reason the body was found at all, the parents were told, as though they should be grateful he had been wearing it.

▴ ▴ ▴

At night, the mother sees the orange helmet winking out from behind the stilt grass, flashes of it in the corner of her eyes, and when she turns she sees him, under the bright cap, the pale stamen of her son drifting, naked boy with his long hair—surely they thought he was a girl when they first came up on him—her darling in the bulrushes.

▴ ▴ ▴

Her son of so many shades. A gelding changing color. Their nonverbal son; their distant, open-mouthed son; their angry, self-absorbed son; their beauty queen son; their supple, warm-skinned son with the long fragrant hair; their stubborn son, barnacled to the steel pole in the supermarket; their ecstatic son, limbs outstretched on a bright fall day outside his grandparent’s house, dancing; all of their sons, all gone, all flown out like swallows into an aperture of severe self-light.

▴ ▴ ▴

He was diagnosed officially by four, suddenly stopped speaking at three-and-a-half, all in a few weeks, a month perhaps, from compound sentences, to phrases, then a few last words, like a good-bye. After that it was only gestures, if anything.

▴ ▴ ▴

Anything, that is how the mother remembers feeling, how acute her anger could become. She would take anything from him. She had never wanted to shake her child, but in those first months of regressive onset, she could not stop herself from asking him, “Thomas? Are you okay? Are you okay? Are you okay?” and how she hated her reliance on that question, how she never said anything else to him those days, only asking, pleading, was he okay in there, was he hurting in there, was he scared in there? Was he okay? Because he seemed in pain, or hurt, the way he scrunched his face, closed so tightly his eyes. And his silence was so awful, and sudden. Are you okay? Are you okay?

▴ ▴ ▴

How she wanted to hurt him, she admits this now, how she wanted to make his agonized gestures correspond to something real, to make his clinched eyes correspond to the world as it was. She wanted to place something hot in his hand and see him do something about it, to see him hurting because of something outside. Something she could then remove, and say, all better, all better. She is not ashamed.

They tickled him, but instead of the normal squeal, the look in the eyes that before had pleaded with delight, “no more,” he would instead go stiff, eyes wide as though listening to something far off.

In the mornings, she would go in to find him manipulating his tongue in his mouth, his eyes clamped shut as though focusing very hard on something. It reminded her of someone trying to tie a cherry stem into a knot, though more involved. Each time she found him this way she would pry the mouth open, convinced and scared he actually had something in there. And it was always empty. Empty and empty and empty. This lovely mouth with its full lips, mouth that had before held songs, and laughter, and such precise little demands.

▴ ▴ ▴

This is autism, she is told, over and over again. This and this and this. The word alone, whenever she hears it or is forced to use it, like a door getting slammed upstairs in a big drafty house, a house growing ever bigger now, big enough to contain all the new things she is fearful of.

The word itself was first used to describe a particular kind of self-absorption noted in schizophrenic patients in 1908. Auto. Self. Selfism. It sounds judgmental to her. Why would you do this to yourself? And then, in the forties, child psychologists decided it was not a form of schizophrenia at all, but something else, some other wilderness of the mind. That’s about as far as they have gotten. And yet, they kept Eugen Bleuler’s troubled word. Autism.

▴ ▴ ▴

His arms swung over his drawn-up knees again, his hands together, his whole body rocking, not wildly rocking, but gracefully, rhythmically, his long fingers interlaced and bumping up and down just so on his shins. His eyes remain fixed to the side, into an empty corner. The eyes are moving as though someone is there, dancing.

Read this piece in its entirety here: https://shenandoahliterary.org/701/now-there-is-only-you/

Delivery Swimming away from the green horizon I foresaw hot light and desiccation sweetened by a swirl of apricot and apple that would soon enough sour. Birds stirred, fluttered my belly. Scenting life, I gave way to gravity. The amber world heaved in a way that was terrible and fun. I was too new to understand paradox— the seasick fish, the cascade of sand. Some tremendous force of love pressed down on my sun-shaped face. I came to know what the amputee knows, leaving behind my perfect self forever. What I didn’t expect was the havoc, the calipers tipped with fire, the rigid god who hung me in air, an aborted sacrifice. The new world closed its rubber hand around me like a tourniquet, dandling me, inverted and wrauling, before the crowd, its roar rasping my brand new skin.

HOUR OF THE GREEN LIGHT is published on January 4th by Future Cycle Press.

HOUR OF THE GREEN LIGHT is published on January 4th by Future Cycle Press.

Helena Fox’s novel HOW IT FEELS TO FLOAT was selected as the winner in the Young Adult Fiction category for the Australian Prime Minister’s Literary Award. The awards celebrate outstanding literary talent in Australia and the valuable contribution Australian writing makes to the nation’s cultural and intellectual life.

Helena Fox’s novel HOW IT FEELS TO FLOAT was selected as the winner in the Young Adult Fiction category for the Australian Prime Minister’s Literary Award. The awards celebrate outstanding literary talent in Australia and the valuable contribution Australian writing makes to the nation’s cultural and intellectual life.

Look at Pictures, Illustrations, Charts, and Graphs 1 Projected on the wall, a map, each school a dot. Colored in codes of the standardized test: there’s basic, taxi-yellowed; proficient, advanced, the colors of wealth. But not my school nor each nearby. In our neighbor- hoods, fire burns, blood pools: below basic, far below basic. 2 At year’s start, the principal talks of who we serve, and who we fail. As always, numbers: far below basic, below, below the tip of the iceberg, metaphorical, blue, in her PowerPoint. This is not, unlike half our staff, new. But then she tapes up photographs on a blank, white board. Shows: This boy, jail. This, expelled. This boy just gone, to where, don’t know. So by the end, it’s nearly half our Black male students. They gaze at us from shadowed portraits, flattened to grainy gray. 3 The young white man presenting has a passion I could squeeze into a drinking glass. He says, For Black students, this is the worst place in the state to get an education. Now I need that drink, its sunshine wedge, to squeeze into the low and fizzing whisper of a G & T, to touch, to eye nothing but glass between my hands, here, where color decides. 4 Some smile, but most practice the shape of hardened mouths and eyes. These boys are gone. We let them down. It’s quick: I start to cry and by the end, I’m shaking, sobs while paisley tissue packs pass round to my sweating hands. How deep, I wonder (don’t ask), will this water get? Far below the iceberg’s metaphor, far past the clink of ice, I see films of the ocean floor I showed my kids, who tried to love nothing, but loved the glow of creatures alive at ocean’s depths. The water’s color, though really none, can reflect blue, brown, or green. If you go deep, its hue looks black. In science, they learn black’s no color. Seep of color’s absence. These boys, lost, are failed and failing. What shade is this disaster, then, what color our failure’s cost?

Poetry faculty member Matthew Olzmann was recently featured in the LEON Literary Review. Read an excerpt of “Fine. I give up. There’s no such thing as trees.” below:

Fine. I give up. There’s no such thing as trees.

You make the two-hour drive back to Marquette for the holiday. At dinner, grandpa asks, “Have you heard the truth about trees?” And you say, “What truth about trees?” And he says, “There’s no such thing as trees; the government replaced them with surveillance machines that look like elms and poplars, but they’re actually highly advanced reconnaissance systems put in place to monitor our thoughts.” And you say, “That’s ridiculous.” And he says, “That’s what they want you to believe.” And you say, “Not everything on the internet is true.” And he says, “That’s what they want you to believe.” And you say, “Not everything is a conspiracy.” And he says, “Just keep on swallowing what they’re feeding you, my dumb little child.” And you say, “I don’t have to listen to this bullshit.” And he says, “Spoken like a loyal pawn of the establishment!” Aunt Beatrice stabs the honey baked ham with her fork but doesn’t eat anything. Uncle Nathan pushes the mashed potatoes from one side of the plate to the other. Buddy asks, “Is it cool if I go check the score of the Packers’ game?” Everyone just stares at him. The dog whimpers under the table. Then grandpa says, “They’re probably listening to us right now.” Buddy says, “Who’s listening to us, the Packers?” Grandpa looks at your mom, and says, “You sure didn’t raise a very bright one here, did you?” And you leap to Buddy’s defense, like you always have, and say, “That is uncalled for, Grandpa. You need to apologize.” And mom says, “Let’s all just calm down a little.” And grandpa says, “How can I be calm when they’ve stolen my liberty?” And you say, “Who has stolen your liberty?” And he says, “Don’t even pretend you don’t know about Obama and what he’s doing to the trees.” And you say, “Obama isn’t even president anymore.” And he says, “That’s what they want you to believe.” And you say, “I’m going outside to smoke.” And mom says, “You’re not going anywhere. We’re not finished with dinner. Can we please just have one nice dinner together? Just one normal dinner as a normal family?” but you push away from the table and head for the door without even grabbing your coat. And grandpa says, “Let him go. The deep state has gotten to him. We’ll have to knock him out later if we want to extract the microchip.” And you close the door behind you, but not before hearing Aunt Bethany saying, “What the fuck?” and Uncle Joseph saying, “This family, I swear to God,” and mom saying, “I spent all day on this casserole,” and grandpa saying, “That’s what they want you to believe.” The door closes. It’s colder outside than you imagined.

Read this piece in its entirety here: http://leonliteraryreview.com/issue-5-matthew-olzmann/

Fiction alum Candace Walsh was recently featured in Entropy Magazine. Read an excerpt of “The Birds: Little Birds” below:

The Birds: Little Birds

Before we were told to avoid air travel, but after the lines at Costco were thirty people deep, the house finches chose our ledge.

Through the window I saw one brindled dun and gray, cream-rimed at her wing’s scallops and striped breast, her mate the same but red-capped and cloaked. Tightly-locused hopping on their splinter-fine feet. Heads domed and darting. My hands washed the dishes with acorn-scented soap. My winter ears drank in their susurrating chirps.

We’d lived in the house less than a year. I thought, it’s lovely to be doing the dishes with a view of a little side porch with a pitched roof, boards painted gray and white with birds to match, our narrow muddy driveway, and beyond that, a grassy field.

* * *

Before there were cases in more than eight states, but after I mixed up a batch of aloe and vodka hand sanitizer because Purell was sold out, I flew to a conference after Helen said, I’m only gonna say it once. I think you should stay home.

Of course I went anyway. She’s the cautious one, I’m the queen of cockamamie schemes. I am the gas and she is the brake. Sometimes I get to bring us someplace far and fast. Sometimes she shuts it all down. Mostly we glide and lurch and rev our way through.

I returned on a Sunday morning red-eye. As always, my absence had sparked Helen’s drive for home improvement in ways my presence dulled.

I painted the mailbox, she said, as if she’d merely cloaked the metal thing with spray paint instead of applying her trompe l’oeil talent and toil to it. She transformed the flat-bottomed metal canister into a mini version of our house: white siding, smoke-gray shutters and window boxes, charcoal-shingled roof.

I imagined her standing out beside it last week in the tall ochre nudged by spring green shoots, as intermittent cars drove by too fast, wearing a baseball hat to thwart the wind’s reckless quest to flop her pewter hair over squinting blue eyes, paint brush in one of her sturdy-fingered hands, palette in the other.

“I love it.” I hugged her. “I’m sorry you stood out in the cold, though.”

“Silly. I unscrewed it from the post and painted it in my studio.”

“So handy,” I said, and she smiled, sun glinting off her right canine.

I went to bed without showering off the air travel taint. When she got in our bed beside me, our lungs quickened and our blood warmed and fluxed. Our bodies were quick to notch us together, slow and then fast, bringing me the last lengths home.

Read this piece in its entirety here: https://entropymag.org/the-birds-little-birds/

Leah De Forest, a 2020 fiction graduate, was recently featured in Bodega. Read an excerpt of “Gifts” below:

Gifts

Sit up straight. Chew carefully. Today is the day you’re meeting them—the family who read about you on a bulletin board and offered to help. They have a long low house designed by an architect (him). Angular windows and muted colors. She, the mother, has styled gray hair and namelessly expensive clothes.

Natural fibers.

Steam-crisp vegetables.

Multigrain bread.

You are eating a salad sandwich, full of crunchy things and juices that gather in the corners of your mouth. Don’t worry, they say. The mayo is homemade.

Today you’re meeting two of them—the mother, Laura, and the youngest daughter, Fi (pronounced fee, short for Aoife, which they pronounce ay-oh-fee). Fi is 14, a year younger than you. You sit in the open-plan promontory of their dining room, which is just off the kitchen, which looks out to the block of nearly-rural land that they live on. Low white-tape fences line the driveway. On the way in your social worker explained that these were electrified, to keep the horses out.

Horses. This close to the suburbs.

They ask you about nothing much. School (you’re good at it). Where you’re living right now (a group home). You swallow hard and dab your mouth and chew the best you can. They are kind. Their house is beautiful, the light clean in a way you’ve never lived before. Laura works at a school and Fi’s three older siblings all have, or are working towards, college degrees. Fi is funny and friendly and has a quick compact smile.

You’re excited by them—by the prospect of them. Life there feels peaceful and settled and smart. No more wrong-brand-name T-shirts or sweaters. In the car afterwards the social worker asks you how it went and you say it was good (you don’t know yet that you’re supposed to say it went well).

At night in your bunk bed you imagine yourself living a shiny life with this new family, the Gardners.

Read the story in its entirety here: http://www.bodegamag.com/articles/509-gifts

Fiction faculty member Peter Orner, along with 2020 fiction graduate Alberto Reyes Morgan, recently discussed “Luvina,” by Juan Rulfo, on Texas Public Radio.

Orner also recently wrote for The Believer. Read an excerpt of “Notes in the Margin (Part V)” below:

Notes in the Margin (Part V)

It’s another scene at the kitchen table in a book of kitchen-table scenes. Morning after morning, night after night, the three of them gather at the kitchen table. I don’t have the novel here. It’s January 2020 and I’m on a bus in New Hampshire, heading home after a funeral.

Some books you don’t need to hold to read.

Marilynne Robinson’s Home. A reader might be forgiven if the kitchen scenes jumble in memory. But the one I am thinking of is unusual because it breaks a certain established pattern and it’s only, if I remember, fifty or sixty pages into the novel. Glory, her brother Jack, and their father, Reverend Boughton, are all at the kitchen table in Gilead. Jack hasn’t been home very long. Maybe a week at this point.

Yet after twenty years (the amount of time Ulysses was away from Ithaca), heis, finally, home. Jack is no Ulysses. He’s been an ordinary failure, mostly down in St. Louis. I’m not sure calling him “prodigal” would be accurate. In my dim recollection of the parable, the prodigal son squanders his inheritance. Though it depends on how you define inheritance: it’s clear that Jack doesn’t have much to squander, at least in a material sense. Brains and charisma, sure, but these he’s still got, even in his current ragged state.

Jack is someone—there are so many—who, once he stumbled, wasn’t able to stop falling down. Glory, too, has limped home. She hasn’t done such a bang-up job out in this misnomer of a real world, either. They’re a family of eight children. The other six are scattered throughout the Midwest, enjoying varying degrees of prosperity. They’ve got kids, jobs, busy lives. Teddy’s a doctor. The others, I forget, but they’re doing better than all right. Glory, though a dedicated teacher, is childless. Her engagement has fallen through. The guy turned out to be a cad. We’re in Iowa during the Eisenhower administration. It makes sense, a spinster daughter returning home to care for her aging father.

So we know why Glory’s come back. But what about Jack? Glory and Jack’s mother died a few years earlier. On the long list of ways in which Jack’s let down the family: he didn’t turn up at her funeral. I can understand it. A funeral’s a tough way to make a reentrance. But why has he now reappeared in Gilead? And after all these years? I’m not sure we ever get an entirely straight answer, and for this I’m grateful. I wonder if there just comes a time, in all our lives, when we wash up at the only door that will open to us.

Read the piece in its entirety here: https://believermag.com/notes-in-the-margin-part-v/