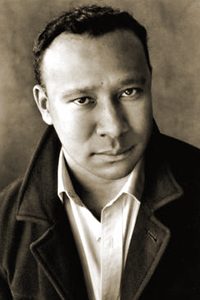

An excerpt from “The Palace” by faculty member Kaveh Akbar published by The New Yorker.

“There are no good kings. / Only beautiful palaces.” Kaveh Akbar’s long poem “The Palace” is both magical and matter-of-fact. The voice is by turn declarative and distraught. The poet invokes Keats, and Keats answers back. “The Palace” also captures the pleasures of everyday life as both a delight and distraction—a simple meal, its possibilities and power. Heaven here is a palace, too: a place not always seen but suffused with wishes. The poem’s leaping form is one of forward-moving fragment and enjambment, of stepping toward and stepping around its chief subject: America.

In Akbar’s poem, America is a country both welcoming and withholding, a land where teens wear T-shirts that promise the obliteration of other places. It is a lettuce spinner, sizzling oil, a goat or a dream on a spit. “The dead keep warm under America / while my mother fries eggplant on a stove,” Akbar writes. There may not be any kings in America, but there are families; there is a father who immigrates, as most do, for opportunity, and a mother for whom opportunity is an earthly garden of goodness. Akbar’s poem is about them, too. Finally, the poem is about love, including the poet’s love for a country in which he is “always elsewhere,” with poetry the ultimate homeland. – Kevin Young, poetry editor for The New Yorker

The Palace

It’s hard to remember who I’m talking to

and why. The palace burns, the palace

is fire

and my throne is comfy and

square.

Remember: the old king invited his subjects into his home

to feast on stores of apple tarts and sweet lamb. To feast on sweet lamb of

stories. He believed

they loved him, that his goodness

had earned him their goodness.

Their goodness dragged him into the street

and tore off

his arms, plucked

his goodness out, plucked his fingers out

like feather.