FOW FORUM

Subscribe to the Friends of Writers Forum and receive notifications of new posts by email.

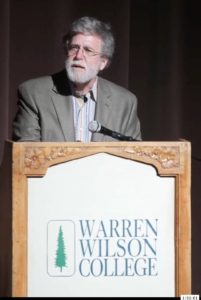

It’s always an honor to have the opportunity to take part in recognizing the achievement of the graduating students.

It’s always an honor to have the opportunity to take part in recognizing the achievement of the graduating students.

Deb is always good about thanking others; I’d like to take this opportunity to thank her, once more, for her extraordinary work during this remarkably challenging residency.*

In my comments on setbacks** earlier in the residency, I talked about the pressure we can feel, from outside voices, to write about some particular topic, or issue, or to write in some particular form. This afternoon I’d like to call on a few of the writers I’ve been reading over the past year, very different writers who have drawn on their own interests and concerns to write engaging, effective, and important work.

The German novelist Jenny Erpenbeck has said, “Growing up, I hadn’t learned that life is a competition, or that it was desirable to be famous, a star, as we are now told day in, day out…The only thing I’d learned was that life is boring if you’re not interested in something….It would be nice if the university weren’t just a gateway to a career, some sort of dues paid…but instead [gave you] time to learn how you live, to learn what matters to you…if the university could be the affirmation of one’s inner life…where those who are seeking have time to get lost, time to take detours…to get excited about something…and sometimes just to lie in the grass…and leave room for thoughts to grow.”

While you’ve worked hard in your two or three years here, and you may not have found many hours to lie in the grass, I hope this time devoted to your writing has in fact offered “the affirmation of your inner life,” and a chance to “learn what matters to you.” I hope you won’t despair, but instead revel in, getting lost. As Saul Bellow once suggested, “Perhaps, getting lost, one should get loster.”

Japanese novelist Yoko Ogawa has said, “Stories are necessary for us to be able to come to terms with our fears and sorrows…”

Only by having a story are people able to connect the body and soul, the outer and inner worlds, the conscious and unconscious, into one. In the form of a story, we are able to put into words the chaos of our deepest darkest places.

To live, then, is to create a story that suits each one of us.

To focus on “the chaos of our deepest, darkest places” is just one option—but in your poems and your stories and novels, I hope you’ll continue to connect body and soul, the outer and inner worlds, the conscious and unconscious, in ways that are meaningful to you.

Michael Ondaatje told an interviewer, “Very early on in my writing life I realized that if you’re going to write, the last thing you should think about is an audience. Otherwise you’re going to give the audience what they want as opposed to what you want to do or discover.

Andrea Lawlor, whose first novel, Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl, was published when they were in their 40’s, agrees: :”I definitely had people in workshops over the years say things like, Well, I felt left out. I didn’t get the references. And I was like, Well, that’s okay with me. I don’t need to explain everything to you. Who am I writing for? Ultimately, the door is open. Anybody who wants in is in. Am I maybe a little bit writing for a Gen X queer person who is happy to complain about how all the good music isn’t on Spotify? Maybe I am; maybe I am writing for that person.

“I think queer and trans writing is so full of joy. Many kinds of joys. We’re people who’ve struggled and fought and sacrificed in the service of desire, self-knowledge, liberation! I mean, what’s more joyful than that? What’s more enviable than that kind of conviction? What’s hotter or more romantic or more revolutionary in spirit?”

My point is not that you should write about the plight of African refugees in Germany, like Jenny Erpenbeck, or about the dangers of authoritarian regimes, like Yoko Ogawa, or a celebration of queer life, like Andrea Lawlor. My point is that the books that move us, surprise us, are often books we couldn’t have anticipated; and they certainly aren’t the product of a writer dutifully responding to anyone telling them what or how to write.

While we’ve given you some requirements to meet, we hope we’ve also helped you gather the tools you need to do something we can’t imagine.

We’ve also given you t-shirts, we’ve given you tote bags, we’ve tried to sell you coffee mugs and environmentally friendly bottles. Today we give you a metaphor.

I know some graduates of this program actually use their walking sticks when they take walks. That’s great. That’s lovely. But—I hope Deb will forgive me—it’s beside the point. I know it’s bad form to explain a figure, but that walking stick you’re getting, it’s not a walking stick. That’s us. And while walking is good exercise—we recommend 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week—there’s a different journey we mean to accompany you on.

By “we” I mean the faculty and fellow students at this residency, yes—but also the other faculty and students you’ve known in this program, the people who have come here to be with you today, the people who wish they could be here, and the people responsible for your being here.

I want to take a moment to recognize all of the people supporting you. They tend to fall into three categories.

First are the People Who Get It. Maybe they read your work and talk to you about it, even make suggestions. Maybe they read some of the poems and stories and novels you do, and talk to you about them. If you didn’t have supporters like that before you came to the program, we know from your comments earlier today that you’ve found some here.

Second are the People Who Want to Get It. When they read your work, they think you’re a genius. They don’t know why you worry so much about revising. They may or may not read the stories and poems you read, but they know your work is better than those other people’s. Some days, we all need that kind of support.

Finally there are the People Who Don’t Get It. They either don’t read your writing or, when they do, they’re puzzled. They may not read much at all. They may worry that you should be spending your writing time doing something regular people do. They worry that you won’t make any money; they worry about all the time you spend alone. And yet—they support you, simply because they know this is important to you. My friends, I confess, there is a special place in my heart for those people, as theirs may be the most generous support of all. Do not take that support for granted, and do not mistake it for something less than it is: blind love.

In closing: I urge you to write from your passion—from your passion–and to draw on the love of those who support you. Tell us what only you can tell us. Whether it’s on Zoom, in person, or on the other side of the printed page, we’ll be listening.

Congratulations.

*In addition to the usual residency challenges, this one saw a number of students and faculty forced to quarantine due to Covid, a record number of bear sightings (never mind a water moccasin sighting), a building on campus being struck by lightning, and a partial collapse of the ceiling of the Canon Lounge.

**As part of the Lifework series, faculty were asked to speak on the subject of Setbacks and Silences.

Dilruba Ahmed

Debra Allbery (Director)

Dean Bakopoulos

Oliver Baez Bendorf

Liam Callanan

Gabrielle Calvocoressi

Daisy Fried

Jennifer Grotz

David Haynes

C.J. Hribal

Vanessa Hua

T. Geronimo Johnson

Sally Keith

Akil Kumarasamy

Sandra Lim

Heather McHugh

Pablo Medina

Antonya Nelson

Alix Ohlin

Michael Parker

Robin Romm

Marisa Silver

Anna Solomon

Daniel Tobin

Connie Voisine

Hello, dear Graduates of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. And welcome, friends and family, to this afternoon and evening of celebration.

Hello, dear Graduates of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. And welcome, friends and family, to this afternoon and evening of celebration.

Along with our stellar faculty, students and all who gather here today, I congratulate you, members of the Class of July 2021, for your accomplishments and for, well, hanging in over these past extraordinary semesters. You have joined the ranks of alums today—At 45 years old, this year, the MFA Program is that much stronger because of you.

Some thanks are due and first, always, to Ellen Bryant Voigt for her poems, essays, teaching, vision and leadership as founder of the first low residency MFA program for writers in the country. Huge thanks to Deb, Trish, and Caleb for bringing us together –without them, we would all be somewhere, but where?

“ I learn by going where I have to go,” says Theodore Roethke in The Waking. To the page is where we have to go, where we learn how to progress from syllable to syllable, word to word, stanza or paragraph to the next. The first utterance demands another and another. And we do not know where the page will take us, of course, because we have never written this poem or story or novel before. But we are compelled to push ahead, and we have had the good fortune to slosh through uncharted territory with each other over the past two or more years. Let me repeat, with each other.

This is your graduation day, yes. But you are not leaving our ever-growing community. This month, nearly100 writers are gathering for the 31st annual alumni conference, the 2nd to be held in Zoom Land, to present papers, facilitate discussion classes, attend workshops and manuscript reviews, give readings and socialize. For the past 30 years, our community has been lovingly supported by Friends of Writers which provides scholarships, fellowships and grants to students, alums, and faculty, thus supporting our ongoing work and play together throughout each year. National and regional events, newsletters, social media, and a dedicated blog trumpet our pre and post grad vitality. You’ve only to respond to calls for participation.

In the months before my graduation, I had a recurrent dream – I was driving along a narrow and winding dirt road. To the left, balancing on a forbiddingly steep green mountain, a flock of men and women, all drinking champagne. To my right, a severe drop that my car kept pulling me toward. And ahead, a friendly meadow into which I steered my car and idled. Night after night I had this dream – both anxiety provoking and calming. On the mountain, my cohort – celebrating. To my right, the drop off. I was leaving the mountain but refusing the cliff to enter that welcoming meadow which I would continue to mow, tame, and let grow wild going forward.

Those with whom I studied and those who are my students and colleagues today are beloved residents of my literary neighborhood. We meet in Swannanoa; we meet in tiny rooms on our computer screens, we bump into each other at bookstores, and cafes. Through social media, we meet on the campaign trail for state representative; we couch surf as we travel, we marvel at the treasures discovered on each other’s trips to the Grand Canyon, Race Point, the Appalachian Trail. We read a poem, a story, an essay, a book.

Lucille Clifton says, “I write out of what I wonder. I think most artists create art in order to explore, not to give the answers. Poetry and art are not about answers to me; they are about questions.” And those questions might frighten us, trip us up, get the better of us. But we have learned, here, together to tackle them – we have learned that we are up to the task. And we have reached out to each other with our questions and concerns about our work. While the struggle is ultimately our own to wrangle with, we can often find relief from those who know just how difficult it can be to put word to page. This community continues to thrive because students, faculty, alums hold fast by continuing to read each other’s work, listen, and care.

So, whether you are writing, or in a dry spell, receiving honors or feeling like no one cares if you ever write again – this community can be counted on to encourage, congratulate, comfort, and console you.

We have certainly learned that the effort is real. We may, at times, need to be reminded of that. Without the semester’s deadlines, residencies, exchanges—we can lose sight of what we came here for. Family, new homes, jobs or joblessness, an HBO binge-worthy series may keep us from our writing practice. But there is always a way to the writing room. Sometimes we can usher ourselves back. Sometimes, we need help — a nudge, if not a shove. Trust in yourself – and if that feels wobbly—trust your literary neighborhood to help you find your way to the page. You have worked so hard. You have earned every word.

Thank you, Class of 2021, for your achievement. And thank you, in advance, for all you will achieve.

The MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College is pleased to announce its faculty for the July-November 2021 semester:

Mia Alvar

Lesley Nneka Arimah

Sally Ball

Robert Boswell

Karen Brennan

Christopher Castellani

Sonya Chung

Daisy Fried

Brooks Haxton

David Haynes

T. Geronimo Johnson

Christine Kitano

Dana Levin

Maurice Manning

Matthew Olzmann

Peter Orner

Hanna Pylväinen

Martha Rhodes

Nicole Sealey

Debra Spark

Lysley Tenorio

Peter Turchi

Alan Williamson